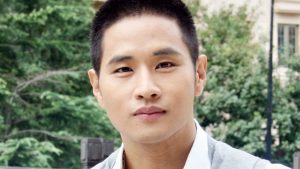

By Byong Il Kim

The author is editor of Digital News Lab of The Korea Daily.

South Korea’s Daegu Mayor Hong Joon-pyo, known for his colorful political career, including his role as the presidential candidate of the Liberty Korea Party in 2017, has a negative reputation within the Korean-American community. During his time as a lawmaker in Korea’s National Assembly, he played a significant role in passing a law that has had a profoundly negative impact on the lives of second-generation Koreans and their families living abroad.

To understand the legislation, we must start with the story of K-pop singer Steve Sueng Jun Yoo. In 1996, this Korean-American singer burst onto the Korean music scene. At the time, he was a permanent resident of the United States who had immigrated to Orange County at the age of 12 and grew up there. Back then, foreign permanent residents were not obligated to serve in the Korean military as long as they stayed in Korea for no more than a year. However, this changed in 2001 when the law was amended. The new decree empowered the Military Manpower Administration to enforce military service on foreign permanent residents if they stayed in Korea for more than 60 days in a year and earned money through performing, broadcasting, appearing in movies, or participating in games.

South Korea was dealing with a draft dodging scandal that had begun in the late 1990s. However, reports at the time revealed that the list of draft dodgers released by a joint investigation team, comprising state prosecutors and military prosecutors, did not include the sons of dignitaries and influential individuals in society. Faced with criticism, the Ministry of National Defense proposed several alternatives, including reducing exemptions for overseas entertainers who faced less social backlash. The government needed a scapegoat to appease public opinion.

In the midst of this, Steve Sueng Jun Yoo continued his activities in the entertainment industry in South Korea. However, in October of that year, he was classified as a public service worker in the physical check-up for military service due to a herniated disc. The public and media, sensitive to the issue of draft dodging, were suspicious, but Yoo stated in multiple interviews that he intended to enlist in the military. A few months later, in January 2002, Yoo renounced his South Korean citizenship and became a U.S. citizen.

South Korean society was devastated, with the media labeling it the “Sueng Jun Yoo Shock,” and the shockwave spread across the nation, leading to outrage. In response, the Military Manpower Administration requested the Ministry of Justice to ban Yoo from entering South Korea.

Capitalizing on this social atmosphere, in 2005, Hong Joon-pyo, who was a member of the National Assembly at the time, proposed an amendment to the Nationality Act, which was subsequently passed. This amendment became known as the ‘Hong Joon-pyo Act.’ It took advantage of the rising antipathy toward those who evaded military service by being born abroad.

Essentially, this law compelled Koreans to renounce their Korean citizenship by the March of the year they turned 18, or else they would be barred from entering the country for 20 years, until they turned 37. Consequently, second and third-generation Koreans born abroad were treated as potential draft dodgers. Previously, second-generation Koreans were not required to renounce their Korean citizenship.

The Korean-American community has repeatedly called for a revision of this law, citing its irrationality and the inconvenience it causes to fellow Koreans living abroad. However, a comprehensive solution has yet to be found.

In September 2020, the Constitutional Court ruled the law unconstitutional due to its ‘excessive prohibition.’ In 2022, an exception clause was added to the Nationality Act, allowing for the exceptional renunciation of nationality for individuals with congenital multiple citizenship. However, this exception only applies to the notification system.

According to a survey, there are approximately 2.5 million Koreans living in the United States, with around 200,000 of them being second and third-generation Koreans. These individuals, known as “congenital dual citizenship holders,” face restrictions on studying or working in Korea due to the Hong Joon-pyo Act. Moreover, their activities in the United States are also limited. They face disadvantages in military academies and key positions within the military. Additionally, they are prohibited from working for federal government agencies that handle intelligence-related work. These restrictions apply to both men and women.

The first priority should be to alleviate the burdens faced by congenital dual citizenship holders. Wrongful laws must be rectified to ensure that second and third generations of immigrants do not harbor resentment towards Korea. Instead of hindering overseas Koreans, the law should be revised to penalize only those who evade military service by being born abroad. The launch of the Overseas Koreans Agency raises high hopes for a resolution to these issues.

![Clovine accelerates global expansion in collaboration platform market Website of Clovine, a cloud-based project management provider [Screenshot]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/0403-clovine-100x70.jpg)

![Hangar images indicate North Korean advances in military drone domain Satellite photos taken on March 28, included in Beyond Parallel's report on North Korea, shows what appears to be seven new drone hangars at the Banghyon Air Base. [SCREEN CATPURE]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/0402-Hangar-100x70.jpg)