[Diaspora Perspective]

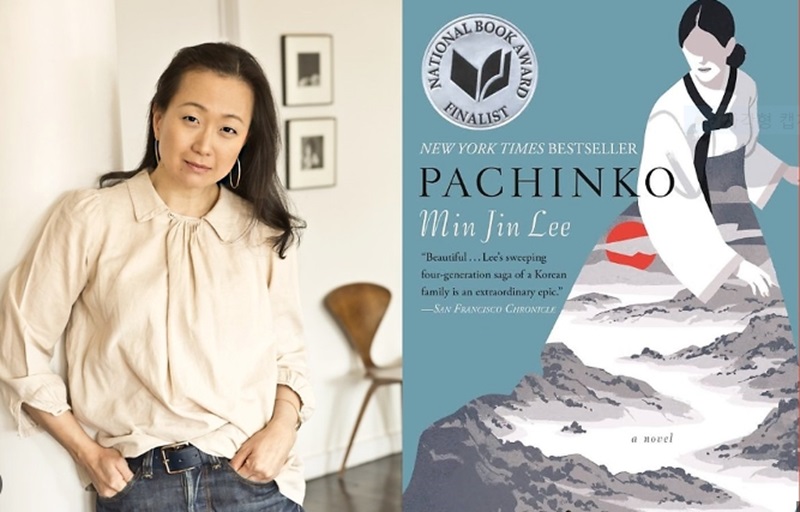

Last year, I had the opportunity to participate in a panel discussion with Min Jin Lee, a Korean-American author who has risen to be one of the most influential writers in America, thanks to works like “Pachinko.” I have always admired Min Jin Lee’s works and, more importantly, her leadership in standing up for the Korean and Asian communities, making the event particularly meaningful for me.

After the panel, I wanted to ask a long-standing question, but with the crowd of students eager to talk to her, I postponed it to another chance. My question was about ‘diasporic identity and worldview.’

Defining a ‘diasporic worldview’ is not easy, but it can roughly be expressed as ‘the capacity to embrace diverse cultures and perspectives, a healthy self-awareness and respect, solidarity with minorities, the ability to understand the complex and multifaceted relationships between the homeland, the place of residence, and other regions, and finally, universal hospitality.’

Min Jin Lee moved from Korea to Queens, New York, at a young age. Growing up as a child of more or less a typical immigrant family, she experienced the clash between Korean traditions and American values. This experience became the backdrop and a crucial backbone of her first novel, “Free Food for Millionaires.”

However, what I find intriguing is her subsequent journey. She lived in Japan with her husband for three years, during which she formed personal relationships with Zainichi Koreans and closely observed their lives. This experience led to the creation of “Pachinko,” which presents a more expansive and complex universe with its intricate character settings and narrative structure compared to her earlier work.

I have a hypothesis that a diasporic worldview becomes clearer when one experiences a third space. Generally, immigrants simultaneously internalize the worldview of their homeland and the country they settle in. Therefore, they can possess a broader perspective than those who live their entire lives in one place, but they may also get trapped in a binary worldview, making errors in absolute value judgments or hierarchical distinctions between the two universes.

For instance, during the production of “Jeronimo,” I observed that most Cubans who sought asylum in the U.S. became staunch conservatives. Having experienced the devastations of communism in Cuba, they seek solutions in the extreme opposite—ultraconservative values, unfettered market economy, and even anti-communism. While one could argue with reasonable objective measures that the U.S. is freer and more prosperous than Cuba, uncritically accepting and defending the myriad problems in America or dismissing efforts to build a fairer society as “communism” is a limitation born of a binary, reductive worldview.

I wondered if Min Jin Lee’s experience in Japan, a third space, might have fundamentally expanded her worldview. Moving from Korea to the U.S. and discovering her identity as a Korean American may have overlapped with the complex life trajectories of Zainichi Koreans, allowing her to objectify her own narrative and shift existing frameworks. Ultimately, I wanted to ask if she was able to “transcend” the label of Korean American or an ethnic minority to become a part of a larger global Korean diaspora, and further, a universal human being.

Just as a point evolves into a plane and the plane into three dimensions, we should consciously seek environments that enable the continuous expansion of our worldview. These environments could be physical, but also intellectual, spiritual, or artistic. By experiencing the third space, we can transform our previously singular or binary perspectives into a more three-dimensional and multifaceted understanding. This broader, more inclusive view helps us move beyond narrow judgments and oppositional choices, allowing us to appreciate the complexity and multiplicity inherent in ourselves and others.

Min Jin, if you are reading this, please enlighten me.

By Joseph Juhn

By Joseph Juhn

The author is a documentary filmmaker of “Jeronimo” and “Chosen”.

![Green card interviews used as decoy for ICE arrests U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents arrest a man after a hearing at an immigration court in Manhattan, New York, on Oct. 27. [REUTERS]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/1226-ICE-100x70.jpg)