August 15 is Gwangbokjeol in Korea, also known as National Liberation Day or translated as the “Restoration of Light Day”.

In an apartment in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City lives a woman who still remembers the cheers of August 15, 1945. Haekyung Lee is King Uichin’s daughter, the Joseon Dynasty’s last royal daughter.

As the granddaughter of King Gojong and the fifth daughter of King Uichin, August 15 has special meaning. Not only was it the day Korea was liberated from thirty-five years of Japanese colonial rule, but it was also the day before her father, King Uichin, passed away and the day her half-brother, Prince Yi Wu, was buried.

“During the funeral of my half-brother, who died from radiation exposure to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945, at Unhyeongung Royal Residence, the Emperor of Japan made a liberation announcement,“ Lee said. “I can still hear all the people who shouted in the streets as I returned home.” On August 16, 1955, the 10th anniversary of the country’s liberation, King Uichin died at the bedside of his daughter, Haekyung Lee.

How did Lee, who once resented her father and tried to erase all memory of him, come to promote the movement to restore his honor? The Korea Daily asked Lee about the anti-Japanese movement of King Uichin, the imperial independence fighter who refused to bow to Japan until the end.

Finding her father’s anti-Japanese activism in a tattered history book

Lee is the oldest of King Uichin’s children alive today. It was when she was working as a librarian. “I couldn’t talk to my father first because of the laws at the palace, and he was almost like a stranger to me,” she said, adding, “I had a lot of resentment towards him because I had heard from others that he was an irresponsible prince who sought alcohol and women.” Lee fled war-torn Korea for the United States in 1956, the year after King Uchin’s death, and after studying voice in Texas, she worked in restaurants and daycare centers to make ends meet before landing a job as a librarian at Columbia University’s Korean Studies Library in New York in 1969. While working as a librarian, Lee unearthed a great deal of material about her father and his anti-Japanese independence movement. After her retirement, Lee started a movement to restore her father’s honor and correct the distorted assessment of her father.

King Uichin’s relationship with Kim Gyu-sik and Ahn Chang-ho began while studying in the U.S.

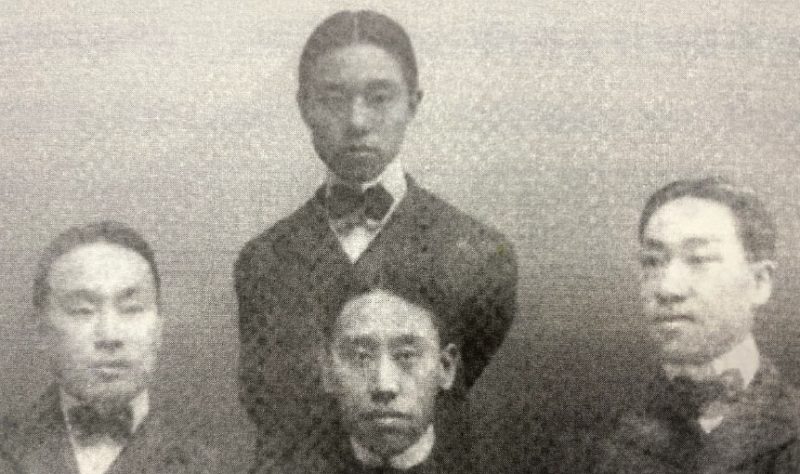

Born in 1877 as the fifth son of King Gojong, King Uichin went to study in the United States in 1899 and attended Roanoke College in Virginia, where he met and befriended independence activist Kim Kyu-sik. In 1902, he traveled to Los Angeles and delivered funds to Ahn Chang-ho, whom he had met through Kim, asking him to “use it for the Korean people in America.”

Supporting the independence movement in secret

After returning to Korea, King Uichin lived under heavy Japanese surveillance, but it could not stop him from secretly contacting and supporting independence activists. In 1909, King Uichin stayed in Geochang, South Gyeongsang Province of Korea for a month and bought land to use as a base for his future righteous army, where he was spotted by Japanese military police and escorted back to Seoul. In 1911, King Uichin met in secret with Son Byung-hee (a member of the 33 national representatives who led the March First Movement), purchased 30,000 square meters of land in Uidong, Seoul, and built the Bonghwanggak Pavilion. In this pavilion, he met with people to discuss the restoration of national sovereignty and conceived the March First Movement. Lee said Lady Kim of Suindang, who lived with her father the longest, told Lee that “whenever King Uichin brought in women for a feast, the rickshaw pullers carrying the women were rebel spies, and they would talk to him in a small room.”

Attempted to escape to join the provisional government in Shanghai

After the failure of the March First Movement, King Uichin realized that independence could not be achieved through peaceful means. He corresponded with General Choi Jin-dong, who had been a commander in the Battle of Bongodong, to discuss the strategy of the independence movement, at which point he realized that “to drive out the Japanese in Korea, we must wage an armed independence movement.” In April, shortly after the March First Movement, the various independence groups joined forces to establish the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, China. Ahn Chang-ho, then the interior minister of the provisional government in Shanghai, planned to send King Uichin into exile in Shanghai. The idea was that if he joined the provisional government, he would serve as an internal spokesperson and would have a great effect at home and abroad, further revitalizing the independence movement. King Uichin told the Shanghai Provisional Government, “I may be a commoner in an independent Korea, but I do not wish to be a nobleman in Japan. I will join the provisional government and devote myself to the independence movement for the sake of my country.” He sent a letter to the provisional government and solidified his decision to defect. However, his attempt to defect was discovered by the Japanese police.

Signing the Declaration of Independence with 33 national leaders

After the attempted escape to Shanghai, King Uichin was pensioned at the Sadonggung Palace. “There was a small glass window in my father’s room, and when I asked my mother about it, she told me that it was a device for Japanese military police to monitor the room at any given time,” Lee explained. However, this did not deter King Uichin. In March 1919, he was elected president of the Daedongdan, a secret independence movement group, and in November of that year, he and 33 others published the Declaration of Independence by King Uichin and others. “We declare to the world that Korea is an independent country,” he said, “and if Japan does not repent of its wrongdoings, we will fight until the last moment.”

The Old Korean Legation’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places

Perhaps it was because she inherited her father’s blood to serve the country. Lee said she would never return to Korea, but she led the movement to correct history and search for lost cultural heritage to restore the honor of the country.

One of them is the movement to return the Old Korean Legation in the United States. It was the first diplomatic mission in Korea’s history to be established in a Western country at King Gojong’s expense but was forcibly acquired by Japan in 1910 for only $5. In response, Lee, along with Kiwon Yoon, a Korean-American living in New Jersey, organized fundraising activities, obtained evidence of the illegal sale and prepared a lawsuit against the Japanese government. On August 7, the National Park Service (NPS) announced that it is collecting comments on the proposal to designate the Old Korean Legation in Washington, D.C., as a National Register of Historic Places. “I’m overwhelmed,” Lee smiled as she heard the news during the interview.

As a child, Lee said she heard her father’s voice all night long as he pounded the floor saying, “I should die.” She added, “We should study the past and not forget how Korea became what it is today,” noting that the country seems to be gradually forgetting the importance of its hard-won independence. “We need to think together about how to protect and live in the country that we have regained. Although we have had many difficulties and challenges, I am proud of Korea.”

BY JIHYE YOON, HOONSIK WOO [yoon.jihye@koreadailyny.com]