By Joseph Juhn

The author is a documentary filmmaker of “Jeronimo” and “Chosen”.

[Diasporic Perspective]

Korea is in turmoil after some conservative political members announced a possible removal of the statute of General Hong Beom-do from the Republic of Korea Army Academy over his past Communist Party membership dating back to 1927. Many intellectuals and the general public, believing this is yet another McCarthyist-style ideological war, are raising opposing voices. One thing missing in the debate, however, is discourse on the uniqueness of the history of Korean diaspora.

In December of last year, I was invited to an event organized by a group of young Koryosaram, Korean diaspora in Central Asia, and visited Almaty, Kazakhstan. Dozens of Koreans from Kazakhstan, Russia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and other countries engaged in discussions on the unique history of Koryosaram and how their narrative could be creatively expressed. They shared stories about events that were crucial in shaping their individual identities as Korean Central Asians.

We visited and paid tribute in front of the statues of Viktor Tsoi, a legendary Korean Russian singer, and Dennis Ten, a Kazakh Olympic figure skater and descendant of Korean Independence fighter who was tragically murdered a few years ago. Then we headed to the Koryo theater. Upon entering the exhibition room, we were greeted by a life-size portrait of General Hong Beom-do. The Koryo Theater, which has fortunately been designated as the National Theater of Kazakhstan in recent years and is now in better condition, in fact thrived for 90 years thanks solely to the sacrificial efforts of the Korean community there.

This was a historic space where General Hong spent his last years as a security guard. The fact that one of the most important Independence fighters who led historic victories over the Japanese imperial army retired as a security guard of a little known community theater reflects the turbulent 20th century of the Korean peninsula.

General Hong Beom-do was born the son of a servant and experienced social oppression and exploitation from a young age. Professor Ban Byeong-yul, an authority on Hong Beom-do, speculates that this background may have had a significant influence on his worldview. Therefore, the Bolshevik Revolution in the Soviet Union may have appeared as an ideal alternative to him at the time of his life.

If General Hong Beom-do’s life and achievements are to be discredited due to his membership in the Communist Party, how should we interpret the complex history of the numerous Koreans who lived in the Soviet Union, their descendants, the Koreans living in China, the Korean Japanese whose allegiance has historically sided with North Korea, and even Koreans in Cuba? Should they also be classified as “communists” or “sympathizers of communism”?

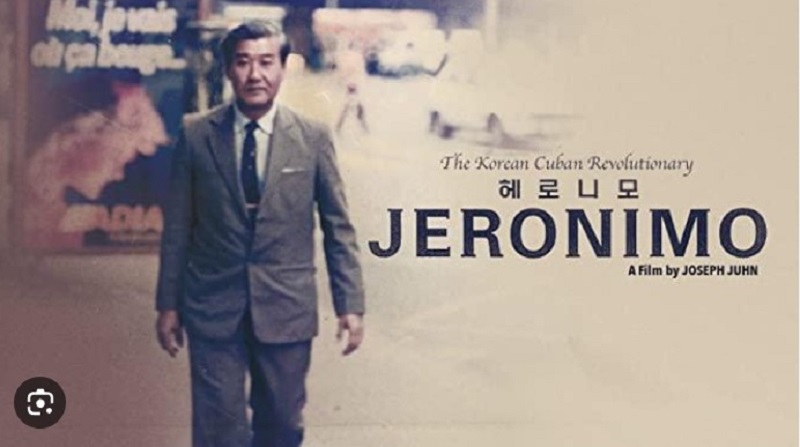

In December 2015, while traveling in Cuba, I happened to meet Patricia, a third-generation Korean Cuban taxi driver. She told me that her father, Jeronimo Lim (Lim Eun-jo) had participated in the Cuban Revolution and later became a Vice Minister in the Castro government. Equally remarkable was her grandfather, Lim Cheon-taek, who was an Independence fighter who had raised funds for the Korean independence movement all the way from Cuba. Lim Cheon-taek was one of one-thousand Koreans who had boarded a ship to Mexico in 1905. However, Mexico was not a heaven on earth they were promised. Some of them immigrated to Cuba in search of a better life.

Koreans in Cuba didn’t fare any better initially. After all, they were stateless people with their homeland seized by Japan. To make matters worse, Koreans were treated like third-class citizens subject to discrimination and unemployment. Then there was the Cuban Revolution in 1959. All of a sudden, so long as they welcomed the new leadership under the socialist banner, Koreans were treated as equal citizens and their quality of life improved. at least until the Castro dictatorship and the collapse of the Soviet Union brought about significant challenges.

In 1995, Jeronimo Lim, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Korean Liberation, was invited by the South Korean government to visit his homeland. Subsequently, he felt a sense of duty to restore the Korean community in Cuba, a dream his late-father had cherished throughout his life. For over a decade, Jeronimo Lim worked tirelessly to reunite Koreans scattered throughout Cuba, establish Korean associations, and build a memorial to honor their ancestors.

The lives of General Hong Beom-do and Jeronimo Lim were not only intertwined with the tumultuous modern history of the Korean Peninsula but were also confined by the political fate of their host countries. As independence activists, revolutionaries, ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union and Cuba, leaders in the Korean diaspora community, the two genuinely sought for their roles in their own respective societies. The directions they chose in life carry a profound and complex weight that cannot be summarized by a few adjectives, like “communist”.

The varied narratives of overseas Koreans represent a valuable asset for Korean history that transcends divisive ideologies. Attempts to categorize them as either “communists” or “democrats” reflect regressive politics. Young Koreans who came together in Kazakhstan, despite the sensitivity surrounding the Russia-Ukraine conflict, opted for unity and solidarity as they shared a collective vision for a brighter future and commemorated their shared historical heritage. Their example serves as a lesson for Korean political leaders, highlighting the importance of fostering unity rather than relying on polarizing rhetoric.