Part 1: The Life of ‘Hero of the Republic’ spy Kim Dong-sik

Infiltration of South Korea, success in contact

[Third is a series]

Infiltrate South Korea, establish contact with ‘Bukaksan’, and return with them. Contact ‘Baegamsan’ and build an underground party organization.

In April 1990, the operational order was issued. Vice Minister (Deputy Minister level) of the Labor Party’s Liaison Department, Lee Won-guk, visited the two-member spy team, led by leader Kwon Joong-hyun and member Kim Dong-sik, and gave direct instructions.

The Leader’s trust and consideration for comrades are great, so we must complete the mission successfully and repay them.

The operation code name was designated as ‘Oseongsan’. Two intense emotions dominated Kim Dong-sik.

First, a sense of liberation washed over him. He had endured nine years of ideological indoctrination and rigorous training since 1981 at the Geumseong Political and Military University (now Kim Jong-il Political and Military University) and five years of sealed and enemy conversion education. The realization of being deployed in actual combat brought a sense of self-fulfillment.

The burden of the infiltration mission also weighed heavily on him. The psychological pressure of having to navigate uncharted territory as a 28-year-old dealing with unfamiliar figures, code-named ‘Bukaksan’ and ‘Baegamsan’, was immense.

Opening Secret Files Containing Bukaksan and Baegamsan’s Identities

Kim Dong-sik accessed classified files. Bukaksan was revealed to be a female sleeper agent active in South Korea for ten years, and Baegamsan was a 30-year-old South Korean politician K recruited by Bukaksan. Kim testified to the ‘North-South Spy War’ reporting team.

[18-year-old Kim Dong-sik: From trainee to human weapon in North-South spy war]

[Special order from Pyongyang: ‘Become a South Korean’ – Espionage training of Kim Dong-sik]

When assigned the mission, the department provided personnel files with real names and activities of Bukaksan and Baegamsan, allowing us to understand their identities thoroughly.

The operation code name was a security measure to replace real names or organization names with codenames. North Korea often used names of mountains and rivers like ‘Bukaksan’ and ‘Seongnamcheon’ or symbolic names like ‘Kwangmyongsong’ and ‘Bonghwa No. 1’. The term ‘movement group’ was used by North Korea’s operations department against the South at that time.

Kim Dong-sik’s team began crafting a tactical plan, or action plan, in earnest.

A small mistake could cost lives. They created virtual scenarios for various unexpected situations during infiltration and practiced responses repeatedly. From essential requirements for operational activities such as identity camouflage, infiltration, contact, recruitment, underground party construction, and radio communication to detailed items like behavior in case of exposure and daily living expenses considering local prices were covered.

The action plan went through rigorous discussions and agreements at each stage by the responsible officer, manager, and deputy director before being finalized. The handwritten action plan was over 300 pages long.

Equipment was provided. Infiltration clothing, guns, bullets, grenades, operational funds, and forged IDs were packed in waterproof balloons. The D-Day for infiltration was all that remained.

The conflict between prolonged infiltration and sexual desire

One intriguing aspect included in the action plan was how to autonomously control sexual desire.

Spies operate undercover for months after infiltrating South Korea. They learn to handle situations in bars, and brothels, and how to use condoms during education.

Spies are human too. They might not resist sexual curiosity or desire in the liberal South Korean society. The action plan needed to consider potential deviations in such cases.

Spies are subjected to physical examinations upon returning from South Korea. Cases of spies contracting sexually transmitted diseases from brothels occasionally surfaced. These individuals faced disgrace and quietly disappeared.

During a meal with the deputy director and some drinks, Kim brought up the issue of controlling sexual impulses. The response was simple.

“What should I do if a woman problem arises in South Korea?” Kim asked.

The Deputy Director said, “Handle it like Sorge did.”

Kim knew of the legendary Soviet spy Richard Sorge (1895-1944). He had even seen the film “Who Are You, Mr. Sorge (Qui êtes-vous, Monsieur Sorge)” about his life.

‘Handle women like the legendary spy Legend Sorge did’

Sorge, a German national fascinated by communism, moved to the Soviet Union and was recruited as a spy. Disguised as a correspondent for a German newspaper, he went to Japan in 1932 and approached the German ambassador to Japan and the Japanese power elite.

In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. By September, Moscow was in grave danger. Stalin hesitated to redeploy Soviet Far East troops facing the Japanese Army in Manchuria to Moscow, fearing a surprise attack by Japan. Sorge’s information was sent to the Soviet intelligence agency.

“The Japanese military will not advance north. They will move south to secure oil resources.”

Stalin deployed the Far East troops to defend Moscow. The German offensive faltered, and they retreated. The Soviet Union was revived.

Sorge’s information turned the tide of World War II. Sorge used women, including the German ambassador’s wife, for gathering secrets and operations. He was executed in a Japanese prison in November 1944.

Kim understood the deputy director’s words to “handle it like Sorge.” It meant to use women actively if necessary during mission execution but not to get involved emotionally.

Departure from Nampo, infiltration of Seogwipo in four days

On May 26, 1990, D-Day arrived. Kwon Joong-hyun and Kim Dong-sik left the Pyongyang guesthouse and boarded a “combat ship” at Nampo Port. It was a 30-meter-long steel vessel equipped with high-performance engines capable of speeds over 40 knots, carrying about 20 highly trained combatants and weapons.

The spy team reached international waters off the southern coast of Jeju Island via China’s Shandong Peninsula in four days. They transferred to a semi-submersible and swam through pitch darkness to land on the coast of Bomok-dong, Seogwipo-si. They told the returning combatants, “Tell them we will complete our mission for the Party and the Leader and return.”

Following the action plan established in North Korea, they marched at night to a cemetery near the KAL Hotel in Seogwipo. They buried their clothes and operational equipment under pine trees. The equipment included two shortwave radios, two Belgian Browning pistols with ammunition, four grenades, and a night vision device. They also buried $50,000 in operational funds separately to be retrieved later for transfer to another spy team in Seoul’s Suyu-dong.

First morning in South Korea, no suspicion of North Korean accent

They faced their first morning in South Korea. They planned to take a taxi to Dongmyung Department Store in Seogwipo. Despite rigorous enemy conversion training, it was their first time in South Korea. They had never conversed with a real South Korean. Kim was nervous about whether the taxi driver would notice his North Korean accent.

Kwon’s accent was strong despite the training, so Kim had to take charge. He mustered courage, rehearsing his lines repeatedly in his head, and boarded the taxi.

“To Dongmyung Department Store, please,” Kim Said. (Kim Dong-sik)

The taxi driver replied, “Sure.”

His Seoul accent worked. The driver did not suspect anything. Kim gained confidence. They moved around Seogwipo, visiting restaurants, cafes, theaters, and department stores before checking into a motel. The first time is always the hardest.

They stayed in Seogwipo for three days, preparing to infiltrate the mainland. They checked if they could carry operational equipment like radios and pistols. After thoroughly checking the conditions at Jeju Passenger Terminal, they decided to abandon the equipment and only take $30,000 of the operational funds.

They traveled by ferry to Mokpo, then by train to Seodaejeon Station, and arrived in Yuseong, unpacking at the “Beolnabi” lodging house near the Riviera Hotel. Ten days after infiltrating South Korea, they became accustomed to the environment and culture. They decided to proceed with one of their objectives: contacting Bukaksan. Kim called Bukaksan from a public phone and arranged to meet. They went to Bukaksan’s house in Daebang-dong, Dongjak-gu, Seoul. They confirmed the contact by checking Bukaksan’s ring. The contact was successful.

Contact with major female sleeper agent Lee Sun-sil

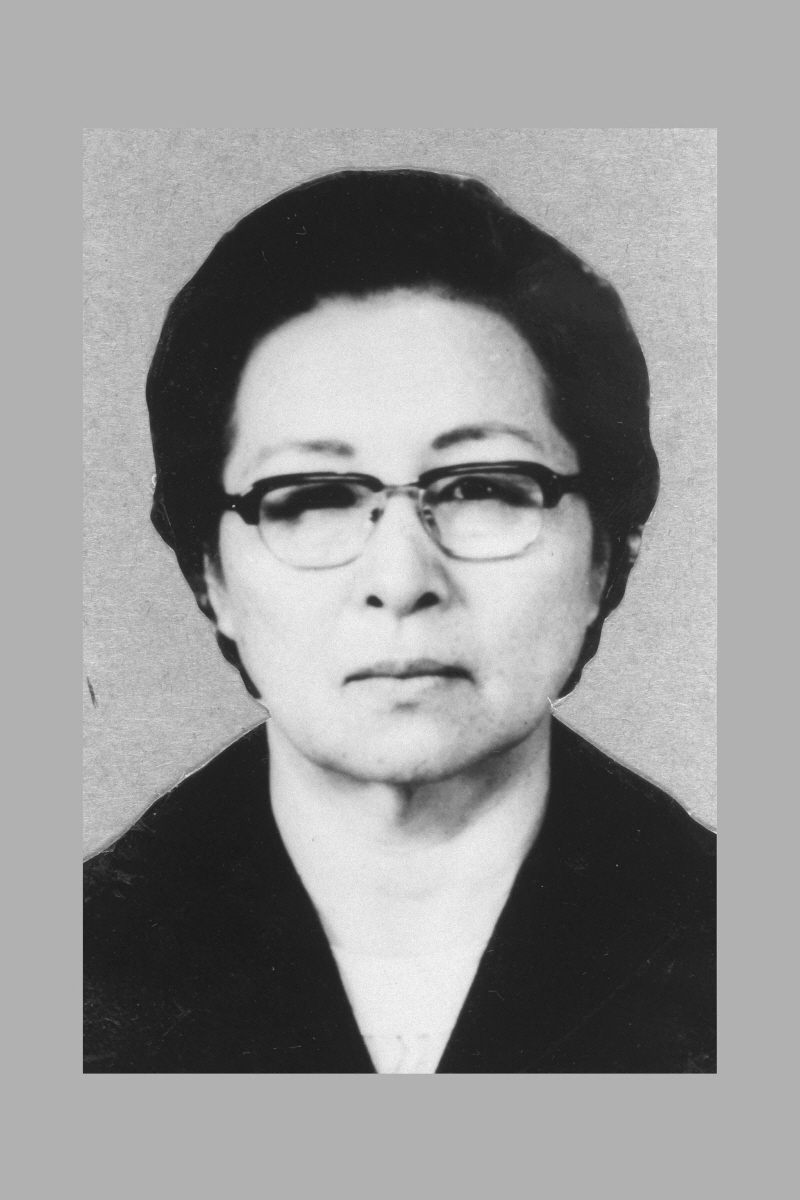

Operation code name Bukaksan was Lee Sun-sil, a major female spy ranked 22nd in the North Korean Labor Party hierarchy. She had been active in South Korea for ten years, but no South Koreans knew her identity. She was 74 years old at the time.

Two years after Kim’s team made contact, South Korea was shaken by the “North Korean Labor Party Central Region Spy Ring Incident” in October 1992. Lee Sun-sil was revealed as the mastermind, gaining the nickname “Grandmother Spy.” However, this was after she had escaped South Korea.

The “Lee Sun-sil file” Kim received in North Korea detailed her background. Born Lee Hwa-sun on Gapado, a small island south of Jeju Island, in November 1916, she adopted the alias Lee Sun-sil when appointed as a candidate member of the Political Bureau at the 6th Labor Party Congress in October 1980.

Lee Sun-sil, influenced by communism before liberation, was active under the guidance of Kim Dal-sam (1923-1950) after liberation. Kim Dal-sam led the Jeju 4.3 incident as the head of the South Korean Labor Party’s Jeju branch and the guerrilla commander before defecting to North Korea.

Appointed by Kim Il-sung as the head of the South Korean region of the Labor Party

After moving to Busan, Lee Sun-sil joined the South Korean Labor Party and served as a women’s alliance officer before fleeing to North Korea. She submitted a petition to Kim Il-sung, stating her desire to dedicate her life to the unification of Korea, and became a spy.

In the 1970s, she infiltrated Japan and repatriated a Korean-Japanese named Shin Soon-nyeo from Jeonju, South Korea. She then assumed Shin’s identity through a ‘legal’ identity laundering, a first in North Korea’s history of operations against the South. Recognized for this unprecedented achievement, she met Kim Il-sung in 1979. Kim praised her for her significant work and gave her further instructions.

“You will go to South Korea and act as the chief of the Labor Party’s South Korean region,” Kim Il-sung said. “Hide for a long time and secure supporters and sympathizers for the revolution.”

In the spring of 1980, Lee Sun-sil officially infiltrated South Korea with the government’s approval for permanent return and began her undercover activities. That October, she was appointed a candidate member of the Political Bureau and in 1982, elected as a delegate to the Supreme People’s Assembly, marking her continuous rise.

Kim Dong-sik’s team disguised themselves as relatives from Jeonju, where Lee Sun-sil’s fake identity Shin Soon-nyeo was from, who had come up for job opportunities. They started their mission in the room they were staying in at her house. Kim described his first impression of Lee Sun-sil to the JoongAng Ilbo, a leading Korean newspaper affiliated with the Korea Daily.

“Living together, I saw that Lee Sun-sil was very intelligent, with a strong pride and stubbornness,” Kim Dong-sik said. “She often lamented that she couldn’t return to North Korea because she hadn’t accomplished anything substantial in ten years.”

(To be continued)

BY DAEHOON KO, MINSANG KIM, YOUNGNAM KIM [ko.daehoon@joongang.co.kr]

![Column: An Era When Green Card Interviews End in Handcuffs (Left) Tae-ha Hwang and wife Xelena Diaz at the USCIS Los Angeles office, where Hwang was detained mid-interview. (Right) The marriage certificate submitted for Hwang’s marriage-based residency petition. The photo has been blurred for privacy reasons. [Courtesy of Xelena Diaz]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/1208-newsletter-Hwang-100x70.jpg)