Block 14 at Lone Fir Cemetery, located in Portland, Oregon, possesses a forgotten chapter of American history. Encircled by imposing barbed wire and heavy chains, this desolate parcel sets itself apart from the rest of the cemetery, whereas other areas are adorned with weathered tombstones draped in dark green moss. Despite the lack of traditional markers, a paradoxical sign boldly asserts, ‘This is not an empty field.’

In its heyday from the late 1800s to the early 1940s, Block 14 was a bustling graveyard with tombstones etched with Chinese characters. This secluded corner, now under a haunting silence, was the final resting place for thousands of Chinese immigrants until it was forgotten by the public. The history woven into the fabric of Block 14 intricately connects with the broader narrative of Asian immigrants in America—a narrative marked by enduring adversity and persistent struggle.

Lone Fir Cemetery is currently under the stewardship of Metro, a regional government agency in Oregon. The management of this historical site is now taking steps to preserve and unveil the long-neglected stories inscribed into the landscape of America’s immigrant past.

Two designs for the memorial garden

On October 21, the air was filled with excitement as officials adorned with Metro name badges set up booths and erected information boards for a public hearing in front of Block 14. The chilly drizzle did not dampen their spirits as they prepared hot coffee and chocolate donuts, resembling a party host bustling to welcome guests. Against the backdrop of the empty land, the atmosphere was warm and inviting, making it hard to resist the urge to join in on the fun. As the preparations finished, people began to trickle into the usually quiet Block 14, creating a cheerful atmosphere that contrasted starkly with its typical serenity.

In Asian culture, cemeteries are spaces of reverence, meant to be solemn, especially in the presence of the dead. The silence before tombstones is an act of honoring and spiritually connecting with the departed. Yet, on that day, Block 14 was about to undergo a remarkable transformation. Approximately 50 people attended the public hearing, exchanging greetings and hugs. Smiles lit up faces, and lively conversations filled the air.

Anita Yap, head of the Multicultural Collaborative, was among the key figures hosting the event. She enthusiastically explained the plan for the memorial garden dedicated to honoring the Chinese immigrants who found their final resting place in Block 14. “We believe it’s important to share the stories behind this project over the years and keep the community informed,” said Yap. “We have been actively reaching out to them to keep the community informed about the progress of this memorial garden project.” The proposed garden, envisioned to be completed by 2026, promised to revive the narrative of this historic plot.

Michael Yun, a memorial designer of mixed Chinese and Scottish heritage, presented two concepts for the memorial garden – “The Grove” and “The Hill.” Each design was a thoughtful reflection of the cultural and immigration history of the early Chinese community in Portland. At his presentation, Yun emphasized storytelling and the importance of creating a space where the struggles and contributions of the immigrants could resonate with visitors. “It is also an opportunity for me to explore my family history and the emotions associated with our transgenerational experience.” Central to his vision was the incorporation of symbolic objects like the ginkgo tree, inspired by its historical significance in Chinese shamanism, and bridging between the past and the present. In fact, the immigration history of Yun’s family began with his grandmother’s moving from Shanghai.

The objectives of this memorial garden included providing a space for acknowledgment, healing, and reality of the challenges faced by immigrants in a foreign land. This touched the hearts of those present who viewed the memorial as an outlet to reclaim and celebrate the stories of those buried in Block 14. While the stories of burying immigrants were still veiled from history, the attendees at the public hearing believed the memorial garden would serve as a trigger of reminding the struggles and sacrifices of early Chinese sojourners who built Portland’s seawall and much of its infrastructure, constructing many of the urban systems we take for granted today.

Burying Block 14’s history under concrete

The history of burial at Block 14 dates back to the 1940s. In 1948, Lone Fir Cemetery was not under the ownership of Metro, but Multnomah County which is home to Portland. The county had plans to repurpose the land of Block 14 and requested the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association to exhume all remaining bodies there. During the process of exhumation, 265 human remains were discovered. Later, the Multnomah County government announced that Block 14 would no longer be used for burying bodies and cleared Block 14 entirely. By 1953, the Morrison Building, a Multnomah County government structure, was erected on the site, and Block 14 disappeared under concrete. It was not just the demolition of the physical structure but also the entombing of the stories of the many immigrants by concrete.

For nearly half a century, Block 14 remained hidden beneath layers of concrete, and its significance as a burial ground for Chinese immigrants gradually faded from public awareness. However, the last flame of memory has not disappeared from the memories of descendants because, in traditional Asian culture, the concept of “memorial service for ancestors” is deeply revered. Family members gather to pay their respects and engage in a form of spiritual communion, placing photos of their ancestors on a table, together with food, flowers, and incense. The air becomes thick with the sweet, smoky scent of incense, and the flickering light of candles illuminates the room. The family members bow in respect and read prayers, expressing gratitude to their ancestors for their guidance and protection. Through this regularly practiced ritual, they honor the memory of their ancestors and keep their spirits alive. It is a meaningful way to connect with the past and celebrate the enduring bonds of family.

The burial ground of Block 14, which was once a core spiritual place for the Chinese immigrant community, now lies under concrete, and the inability to perform ancestral rituals on their resting ground has spread a sense of guilt and unwashable grief among the descendants of those buried there.

Although the ownership of Lone Fir Cemetery eventually shifted from Multnomah County to Metro in 1997, the transfer did not include Block 14, as the Morrison Building, which belonged to the county government, still occupied the site. As a result, even with its historical significance, Block 14 remained in the shadows.

Backlash against the development plan

In 2004, Multnomah County announced a plan to demolish the Morrison Building constructed on Block 14 and sell the land for a condominium complex, which posed an irrevocable threat to the sealed history of Block 14. The Chinese community, fearing the permanent loss of their ancestors’ immigration history, strongly opposed this plan.

Lone Fir Cemetery symbolizes the history of Portland as well. The cemetery hosts the graves of local celebrities, including Asa Lovejoy, a founder of the city of Portland, and Dr. James C. Hawthorne. The Chinese immigrants interred in Block 14 are also an essential part of this history, as witnessed by Hannah Erickson from Metro, overseeing the Block 14 Memorial Garden project, “Chinese people have significantly contributed to the development of Oregon. However, their history, especially the harms against them, has often been overlooked.”

The proposed development plan encountered fierce backlash, drawing not only criticism from the Chinese community but also resistance from local residents and the Friends of Lone Fir Cemetery. Concerns were widespread, with many asserting that human remains were still interred in Block 14. Marcus Lee, a member of the Portland Lee’s Association, claimed: “When we learned about the development, we insisted that remains were still there. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association even brought out a burial ledger to prove it.”

Maria Rojo de Steffey, Commissioner of Multnomah County at the time, commissioned Archaeological Investigations Northwest in Portland to conduct an archaeological survey during the demolition of the Morrison Building. This action was taken to verify claims from Chinese immigrants and local residents who argued that human remains might still be present in Block 14.

Helen Ying, current president of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, has a unique perspective on the events of January 2005, as her husband, Stephen Ying, was the president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association at that time. She recalls, “The survey uncovered remains of at least two individuals, confirming that Block 14 still has human remains. This discovery supported the importance of not disturbing this sacred burial ground.”

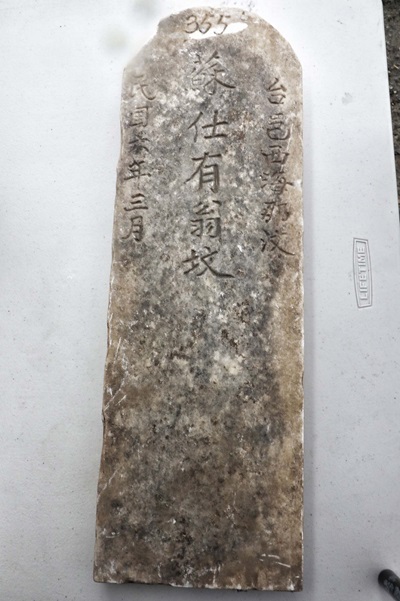

Block 14 was more than a burial site for both the Chinese and local communities. It was a nexus of cultural and spiritual significance, with bone houses, funerary burners, and altars, weaving intricate layers of meaning for those connected to it. The discovery of tombstones and funerary tools halted all development plans.

15 years of effort to excavate the immigrant history

Recognizing its historical value, Multnomah County transferred Block 14 to Metro in 2007, reintegrating its entombed stories back into the narrative of Lone Fir Cemetery. Erickson noted, “Block 14 is a symbol of how Asian American contributions have often been erased from U.S. history.”

The challenge then shifted to recovering and preserving Block 14 as a historical landmark. In 2011, the Chinese community established the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation to maintain the site and integrate its story with the cemetery’s broader history. Their dedication aimed to ensure visitors to Lone Fir Cemetery engage with the project to create a memorial garden at Block 14.

However, funding was a challenge. The Chinese community’s efforts to raise funds were insufficient to construct the memorial garden, presenting a substantial hurdle to preserving this significant piece of immigrant history.

The long-awaited memorial garden project at Block 14 reached a pivotal moment in 2019. The Chinese community received encouraging news when voters in Multnomah, Clackamas, and Washington counties with which Metro is affiliated approved Metro’s $475 million bond measures to protect clean water, restore fish and wildlife habitat, and naturalize lands and local parks. As this initiative aligned perfectly with their vision for the memorial garden at Block 14, the Chinese community reached out to Metro staff to convince their cause. In retrospect of the process, Ying stated: “The passage of the measure was just the beginning. It didn’t automatically allocate funds to our project. We had to engage in a lot of education, both with the public and government staff. Finally, our efforts bore fruit, and we secured the funding. It’s incredibly exciting. We now can have at least a conceptual design for the garden.”

With $4 million from Metro’s bond funding, the memorial garden project at Block 14 became a reality 15 years after the Chinese community’s initial effort to halt the city’s development plan. The stories of Block 14, long buried, are now being unearthed and retold. This project marks a significant step in rewriting the forgotten history.

Archaeological survey to excavate the past

In 2021, as the memorial garden project was initiated to take shape in partnership with the Chinese community, Metro commissioned Dudek, an archaeological survey company, to conduct a comprehensive investigation of Block 14’s history. Numerous unverified stories and rumors had circulated about Block 14 for years, including claims that it was once owned by a railroad company and that approximately 1,000 Chinese people were buried there. Therefore, gathering historical facts was a critical first step before constructing memorial monuments, and a key task of this process was identifying the exact number of Chinese immigrants interred in Block 14.

The Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, founded in 1890, has functioned as more than a mere friendly society for immigrants. It has been a mothering organization where individuals of the same ethnicity uphold their cultural identity and support one another in the face of the challenges posed by living in the United States. This solidarity extended even in matters of death.

Neil Lee, president of the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, explains, “Our role was significant. We helped bury members of the Chinese community. Following cultural traditions, some of them were later disinterred, their bones placed in boxes, and sent back to their homeland. We have detailed ledgers of people buried and disinterred here.”

Dudek exhaustively reviewed all burial records provided by the Chinese community, processing the challenging task of translating old Chinese handwriting into modern script. A comprehensive report detailing the findings is expected to be released later this year.

Based on the preliminary findings from the review of burial records and Metro’s data spanning from 1867 to 1927, at least 2,892 Chinese immigrants were buried in Block 14. They primarily worked in Oregon’s railroad labor, canneries, mines, and farms, forming a significant part of the state’s early workforce.

Beyond its role in commemorating the past, the memorial garden project seeks to foster a sense of community and connection to its cultural roots. One example of this is the Qingming Festival, also known as Tomb Sweeping Day, which has evolved into a community gathering at Lone Fir Cemetery where people come together to honor their ancestors.

Metro’s Hannah Erickson, a public relations specialist for the Block 14 Memorial Garden project at Metro, stressed the significance of Chinese labor in shaping Oregon. She specifically highlighted the need to acknowledge and remember both the contributions and hardships of Chinese and Chinese American people, but often overshadowed by dominant white culture. “Dominant white culture has been unwilling to remember the fact, nor the harm perpetrated against Chinese and Chinese American people. Block 14 of Lone Fir Cemetery tells a story of erasure.”

The story of Block 14 echoes a broader narrative of immigrant recognition in American history. Its preservation demonstrates the importance of acknowledging and valuing the diverse narratives in our shared past. The memorial garden, once completed, will stand as a place for Chinese Americans to reconnect with their history and practice traditional cultural expressions of honor. This also signifies the unveiling of the histories of other Asian communities in the United States.

During the public hearing to select the final design for the memorial garden, attendees could not hide their delight. The site was filled with noticeable excitement, and the air was charged with anticipation, projecting the communal joy of the moment as they eagerly awaited the future of the memorial space.

However, despite the notable progress in constructing the memorial garden, concern about their community persisted among Chinese people at the hearing and in Portland as a whole. The concern was due to both the present and the future of their community.

The Quest for Cultural Continuity: Portland’s Chinatown Identity Dilemma

A visit to Chinatown, just two miles west of Lone Fir Cemetery, provides a firsthand glimpse into the concern shared within the Chinese community. The Chinatown in Portland, once the second largest in the West after San Francisco, was a bastion for immigrants, providing community, identity preservation, and mutual support. Undoubtedly, building such neighborhoods has never been easy. Nevertheless, the challenges of the once-flourishing Chinatown are evident today. “The Chinese were often driven out of areas by existing residents, including whites. Many came to Portland seeking refuge after being expelled from places like Tacoma, Seattle, and East Portland Tabor,” recalls Marcus Lee. “Chinatown is currently struggling, fighting to maintain its identity and prevent its loss.”

Today, Portland’s Chinatown is not as vibrant as it used to be. Once bustling with tourists and weekend events, it now stands as a shadow of its past. Youngja Kim, who has run Old Town Grocery & Deli in Chinatown for 20 years, reflects on the change: “Over a decade ago, most Chinese restaurants packed up and left. Now, calling this place Chinatown kinda feels like a nod to a bygone era.”

The neighborhood, once a bustling area of Chinese immigrants, now features empty buildings and the presence of homeless people. Closed businesses and padlocks are a common sight in broad daylight, with few restaurants still operating. A front window of a red brick building in Chinatown now displays faded photos and descriptions of You Yee’s family history since the 1930s. The exhibit details the life of a widow who lost her husband, Kai Young Wong, a Chinese herbalist. Left to raise her children alone, she ran a dry cleaner, diligently tailoring clothes more than just what her customers requested. Explaining her family’s immigration history, she remarked, “This archive represents the resilience and societal contributions of several generations of Chinese American immigrants.”

Throughout Chinatown, similar stories of immigrants are plastered on the walls of vacant buildings. These cultural artifacts, adorning weathered walls, tell the stories of their lives as immigrants. Yet, their stories remain largely unheard, as few visit Chinatown to read and understand the rich histories of its immigrants.

The Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association building, a longstanding landmark in Chinatown, has secured its place as it was registered as a national historic place by the United States Department of the Interior. More than just a structure, it houses photographs, ethnic attire, traditional masks, aged documents, such as ledgers detailing Chinese immigrants buried in Block 14, and iron urns containing bone meal of cremated remains.

Neil Lee explains, “Chinese immigrants have a longstanding history and are now dispersed all over the states, and it is important for us to preserve our immigration history to keep our cultural heritages.”

The Chinese Community’s continuing efforts to save Block 14 of Lone Fir Cemetery showcase their dedicated commitment to preserving history even amid the fading vibrancy of Chinatown. Yet, conserving the legacy of immigrant communities is not a responsibility exclusive to specific communities. It requires widespread recognition and understanding of immigrants as integral to multicultural American history. The story of Block 14 in Lone Fir Cemetery is not just a relic of the past. It still deeply resonates with and influences today’s American society.

By Ryan Yeol Jang, Sangjin Kim, Mooyoung Lee (The Korea Daily) and Do Kyun David Kim (Professor at the Univ. of Louisiana at Lafayette)

[jang.yeol@koreadaily.com]