[The Korea Daily is offering the 568-page “U.S.-Korean Diplomatic Crossroads” for free to the first 30 readers who apply, one copy per person. Applications will only be accepted via email (jservicela@koreadaily.com). Please be sure to include your name, address, and phone number. Those who receive a confirmation can pick up the book at our office (690 Wilshire Pl, LA, CA 90005). For U.S. residents, we also offer shipping for a $20 fee.–Ed]

[Book Review]

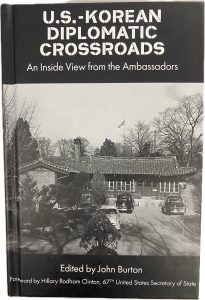

“U.S.-Korean Diplomatic Crossroads” published by KEI

18 former ambassadors reflect on key turning points in relations

A valuable contribution to understanding modern Korean history

Ahead of the launch of the second term of the Trump administration, there are mixed forecasts about South Korea-U.S. relations. Concerns and fears are growing. This is due to anticipated significant changes in sensitive security and trade policies.

That said, there is no need to be overly pessimistic as if the South Korea-U.S. relationship is about to fall apart. The relationship has never always been smooth in the past. There were times when suspicion outweighed trust, and pressure prevailed over respect. While the destination of peace and prosperity was the same, the road to it was not a smooth new highway, but a bumpy rocky path. Still, the South Korea-U.S. alliance continued, and it cannot be denied that this was crucial to South Korea’s prosperity.

Looking back at the history of the South Korea-U.S. relationship, it is natural to gain some insight into the future. A recent publication from the Korea Economic Institute (KEI) in Washington, D.C., titled “U.S.-Korean Diplomatic Crossroads” is a perfect fit for this.

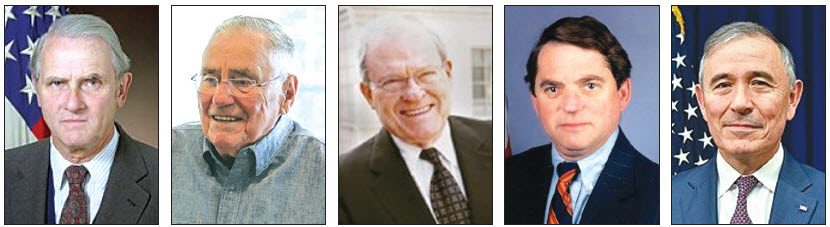

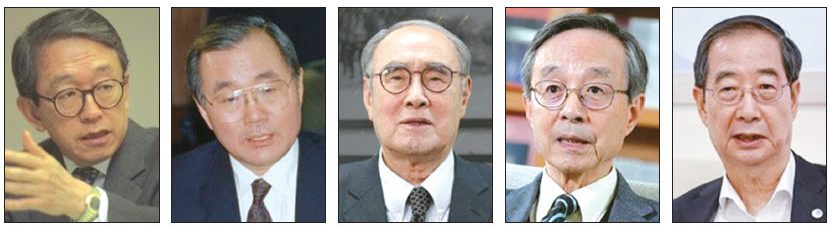

This book is a revised and expanded version of the 2009 publication “Ambassadors’ Memoirs: U.S. Korean Relations Through the Eyes of the Ambassadors.” It is edited in a way where 18 ambassadors, nine from each country, alternately record their experiences on the diplomatic front. The activities of other ambassadors are summarized by others, including John Burton, a former Financial Times Seoul bureau chief.

Rather than relying on hearsay or secondhand information, each ambassador shares their personal experiences through a first-person narrative. In this sense, the 568-page English edition holds significant historical value.

Rather than relying on hearsay or secondhand information, each ambassador shares their personal experiences through a first-person narrative. In this sense, the 568-page English edition holds significant historical value.

There are many lesser-known behind-the-scenes stories from key turning points in modern Korean history. It conveys a vividness and immediacy comparable to the bestseller “The Two Koreas” by Don Oberdorfer of Washington Post.

The book covers nearly 70 years of diplomatic history, from Presidents Syngman Rhee and Harry S. Truman in 1948 to Presidents Moon Jae-in and Trump. While one could choose to focus on specific issues of interest, reading it in chronological order provides a clearer understanding of the major trends.

The role of the U.S. in promoting democracy during the Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan eras, support for the Northern Policy during the Roh Tae-woo administration, North Korea’s nuclear development and the U.S.-South Korea response, the eruption of anti-American sentiment and diplomatic conflicts, and the Trump administration’s engagement with North Korea, among others…

The dilemma between democracy and security

In a 1986 Senate confirmation hearing, Senator John Kerry asked James Lilley, who was nominated as U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, “What do you place first: security or democracy?” Facing this blunt question that forced a choice between the two, Lilley responded, “I am all for bringing democracy to South Korea. But first we have to stabilize the security perimeter in the north and make it clear to South Korea that we support them.”

Before the democratization of South Korea, U.S. ambassadors had to struggle with how to balance democracy and security. This was because strong pressure to encourage democratization or, conversely, tacit approval of dictatorship had each led to adverse effects in the past. Examples include Park Chung-hee’s attempts to develop nuclear weapons, provocations from North Korea, and anti-American sentiment among South Koreans.

Chapters 2 to 6 of the book, which cover U.S. ambassadors during the Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan eras—Philip Habib (1971–74), Richard Sneider (1974–78), William Gleysteen (1978–81), Richard Walker (1981–86), and James Lilley (1986–89)—detail these struggles and frustrations.

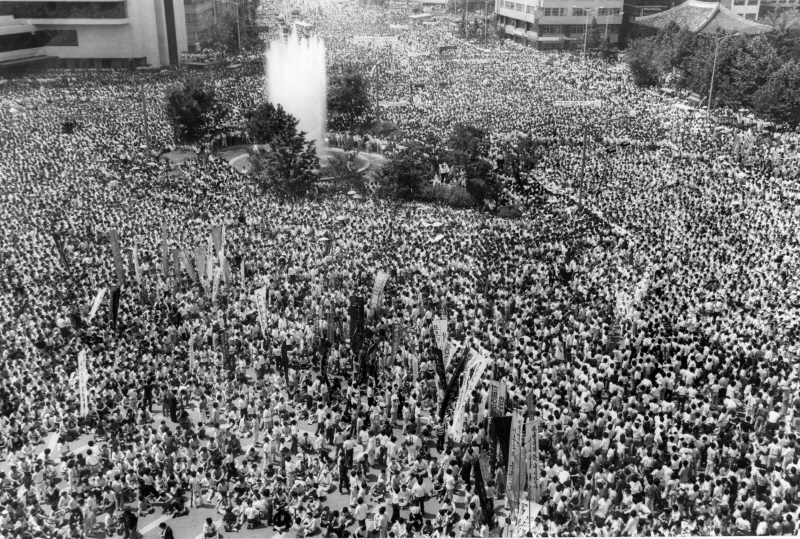

Of course, many South Koreans still believe that the U.S. turned a blind eye to military dictatorship. Left-wing groups, in particular, take such conspiracy theories as fact. However, it is impossible to ignore the role the U.S. played in the June 29 Declaration that came at the end of the Chun Doo-hwan administration. At that time, Chun was prepared to suppress the democratic protests, even at the cost of a second Gwangju massacre incident. The book dramatizes Ambassador Lilley’s efforts to prevent this.

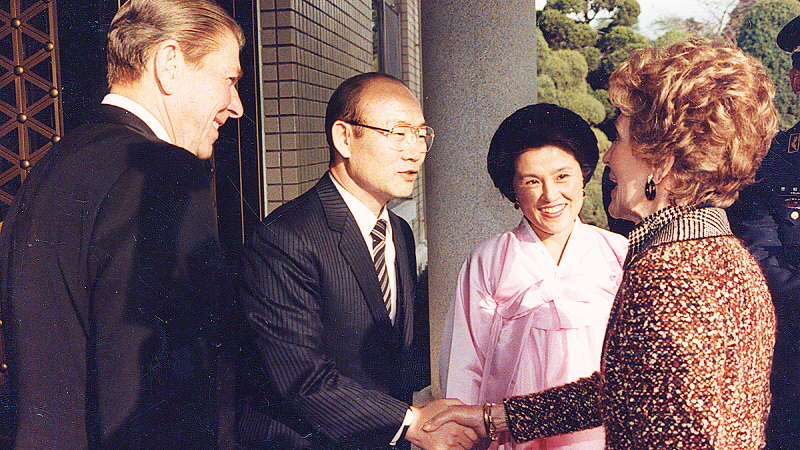

Lilley brought a letter from President Ronald Reagan, gently urging democratization, and met with Chun Doo-hwan on June 19, 1987. Lilley handed the letter directly to Chun, following the advice of Korea’s Ambassador to the U.S., Kim Kyung-won (1985–88), who suggested that a direct, forceful message stating that the declaration of martial law and the use of military force would harm South Korea-U.S. relations would be the most effective approach.

Kim Kyung-won, who had previously served as Chun Doo-hwan’s chief of staff before his posting as ambassador, believed that merely sending a letter through regular diplomatic channels would be ineffective, and Lilley highly valued Kim’s seasoned, intuitive judgment.

Foreign Minister Choi Kwang-soo (1986–88), who accompanied Lilley to the meeting, later whispered to him, “I hope there will be a good outcome.” Shortly after, Chun Doo-hwan abandoned the martial law card, and the wheels of democratization began to roll again. When the news broke, a Korean-American secretary at the U.S. embassy was so moved that she embraced Lilley in the embassy corridor and thanked him, saying, “Thank you for helping to stop it from happening.”

Roh Tae-woo considering taking refuge in the U.S. Embassy

Even after that, the tense situation continued daily until the June 29 Declaration was announced. In the midst of the chaos, Roh Tae-woo, who had fallen out of favor with Chun Doo-hwan, was reportedly so fearful that he even considered taking refuge in the U.S. Embassy.

This was revealed by Lilley, who learned about it from Roh’s close aide after meeting with him privately on June 25. Lilly added, “Others deny this,” but he did not personally verify Roh Tae-woo’s plan to seek refuge. Nevertheless, he reported to Washington that “Roh might be getting wobbly.”

The June 29 Declaration was fundamentally a response to the South Korean people’s demands for democratization, but many forces were at play in its realization. U.S. involvement through Lilley was one of those forces. Lilley introduced part of a farewell telegram he received from U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, who was about to resign in December 1988:

“It is rare that an ambassador can identify one act, or one day, by which he made an historic contribution. You are one of those – at a most critical juncture, in June 1987 as the tragic prospect of martial law loomed over the Republic, your personal intervention with the ROK President undoubtedly made a significant contribution to his decision not to draw the sword.”

Following Lilley, Donald Gregg (1989–93), who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, fully supported Roh Tae-woo’s Nordpolitik, or Northern Policy. Gregg’s extensive network from his CIA career and his close relationship with President George H. W. Bush greatly benefited South Korea’s northern diplomacy.

Bush arranged the 1990 meeting between Roh Tae-woo and Mikhail Gorbachev in San Francisco, which led to South Korea’s recognition of Russia the following year, according to Gregg. Additionally, he said Bush strongly persuaded China to approve South Korea’s recognition in 1992.

This close U.S.-South Korea cooperation was significantly influenced by the friendship between Roh Tae-woo and Bush, which was also reflected in their “tennis diplomacy.” In July 1991, when Roh visited the United States, a tennis match was scheduled between him and Bush.

Diplomatic consultations were held about the format of the game. Gregg and South Korean Ambassador to U.S. Hyun Hong-choo (1991–93) agreed that the two presidents would play as a team, while the two ambassadors would form another team for a doubles match. This was based on the assumption that it would be awkward if the presidents faced each other, regardless of who won.

The match ended with both ambassadors subtly losing. U.S. Vice President Dan Quayle joked, “The two ambassadors made career-enhancing decisions as to how the match came out.” Hyun’s recollections match those of Gregg.

Subtle discrepancies in North Korea Policy

There are unavoidable differences in the U.S. and South Korea’s approach to North Korea, especially regarding North Korea’s nuclear program. According to Ambassadors Hyun Hong-choo and James Laney (1993-97), the U.S. deals with the issue in the context of the global non-proliferation framework, while South Korea views it primarily as a security issue between the two Koreas. This difference in approach has sometimes led to misunderstandings and conflicts between the two countries.

Moreover, Gregg points out mistakes made by the U.S. government. He believes that the breakdown of the conciliatory mood that seemed to emerge following the 1991 North-South Basic Agreement was due to the U.S.

The two countries had agreed not to conduct the joint military exercises, “Team Spirit,” in 1992, but the U.S. Department of Defense broke this agreement. The announcement of the resumption of Team Spirit in the fall of 1992, according to Gregg, was a decision made by Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. “Secretary Dick Cheney reinstated the exercise without consulting either me or the State Department.”

Gregg referred to this as “the single biggest mistake made by the U.S. during my time as ambassador.” He further criticized Cheney, saying, “This was only the first of several destructive moves Cheney later made as Vice President to undercut any move toward reconciliation with North Korea.”

It’s notable that Gregg openly criticized Cheney by name, a rare move for a former ambassador. As he pointed out, after this, inter-Korean relations rapidly deteriorated, and in 1993, North Korea withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). He expressed regret, saying, “The prospects for a major reconciliation were higher than ever before. Unfortunately, this happy period did not last long.”

Efforts to avoid war

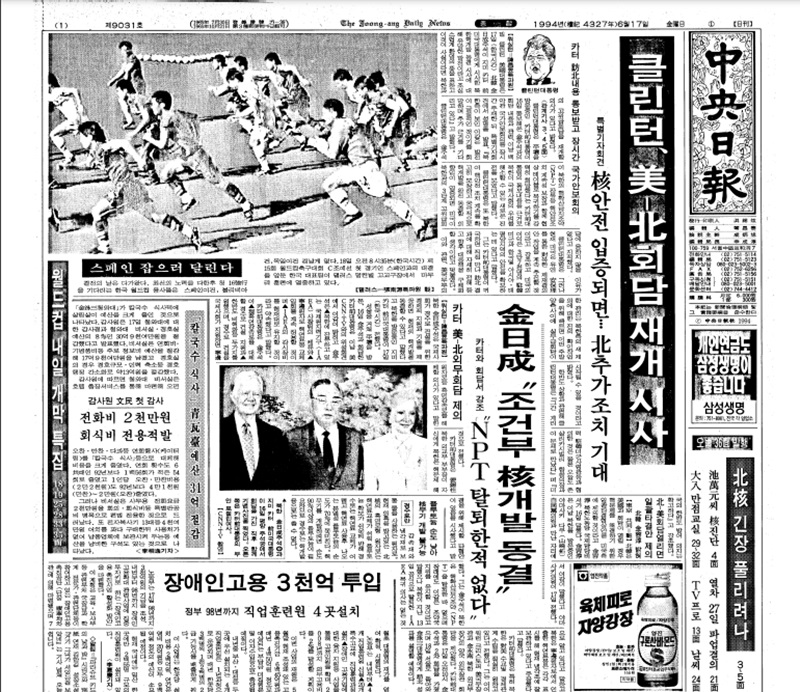

In March 1994, tensions escalated due to North Korea’s nuclear development. During a South-North working-level contact meeting, a North Korean representative threatened that “Seoul will turn into a sea of fire.” At this time, the Korean Peninsula was closer to war than at any point since the armistice in 1953.

Reflecting this, Ambassador James Laney titled his writing “Defusing a Crisis.” As both North-South and U.S.-North Korea talks failed to yield results, hardliners in the U.S. argued for bombing North Korean nuclear facilities. Laney noted, “This idea seemed absurd not only to me but also to our military advisors.”

He traced the cause of North Korea’s nuclear development to the growing disparity between the North and South and the weakening of North Korea’s conventional military strength. Laney argued that, having no chance in a conventional war, North Korea saw nuclear weapons as the only way to ensure its security. He even described North Korea’s nuclear armament as a source of pride.

Though this might seem like an attempt to justify North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, there is no need for an overreaction. Thirty years ago, Laney predicted that North Korea would not give up its nuclear program due to external pressure, and in the end, that prediction became reality.

Laney points out that at that time, both South Korea and the U.S. were in a situation where they could not move forward or backward. The Kim Young-sam administration did not want to provoke North Korea, nor did they want the U.S. to deal directly with North Korea, bypassing South Korea. From the U.S. perspective, it seemed like South Korea was unwilling to take any action.

The turning point came with the well-known summit between former President Jimmy Carter and Kim Il-sung. Laney explained, “President [Bill] Clinton was less than enthusiastic about the idea, but he gave his approval.”

In June 1994, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visited Pyongyang, where he met with North Korean leader Kim Il-sung. During the meeting, they reached an agreement to freeze North Korea’s nuclear program, with the condition that the country would rejoin the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and allow the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to monitor the freeze on-site. In exchange, the U.S. agreed to halt recommendations for further sanctions and promised to assist in building light-water nuclear reactors for North Korea.

While the crisis was defused, the problem was that sitting President Clinton was sidelined. Laney recalled, “He appeared to go beyond his authority by promising what only the U.S. Government could officially do.”

“The White House wanted him to return directly to his home in Plains, Georgia, not to Washington D.C. A furious Carter, after a heated exchange with Vice President Albert Gore, went back to Washington anyway for a debriefing but was largely snubbed on his arrival by all the top officials.”

Differing perceptions of North Korea among U.S. ambassadors

The perspectives of U.S. ambassadors who have served in South Korea on North Korea are surprisingly diverse. Some have tried to understand North Korea, while others believe in dealing with it based on strong power. The spectrum of views is quite broad.

Gregg reflected that through his meetings with the citizens of Gwangju, he developed an understanding of the Korean sentiment of “han [resentment or sorrow].” He shared a similar impression during his visit to Pyongyang. He believed that people in both Gwangju and Pyongyang were not fanatic zealots but ordinary Koreans, and that if he showed them respect, they would respond to his humanity.

In contrast, James Laney described North Korea as a country with a strong sense of national pride. He saw that national pride was personified in Kim Il-sung, and that any insult or threat to him could bring disaster to the Korean Peninsula.

On the other hand, military veteran Harry Harris, who served as U.S. Ambassador to South Korea from 2018 to 2021, believed that military deterrence was necessary for dialogue with North Korea. He argued that diplomacy cannot rely solely on the goodwill of the other party or our hopes, especially when dealing with North Korea.

There’s no need to debate whose opinion is right. Each ambassador made their judgment based on their respective experiences and the situation during their tenure. While Gregg and Laney might have viewed North Korea as a country that needed understanding during their time, Harris likely saw it as a hereditary dictatorship that must be dealt with based on power.

Ironically, Gregg and Laney, who were more accommodating towards North Korea, served during the conservative governments of Roh Tae-woo and Kim Young-sam, while Harris, a conservative figure, was posted during the progressive government of Moon Jae-in.

In particular, Harris revealed that his time as ambassador was difficult because he was caught between South Korea’s progressive president and the conservative president of the U.S. (Trump). He mentioned that he advocated for stronger sanctions against North Korea, presented a cautious stance on South Korea’s push for inter-Korean dialogue, and argued for the enhancement of joint military exercises. These positions, he noted, likely led the South Korean government to be “unhappy” with him.

At the end of his reflections, Harris wrote that he learned some South Koreans prioritize reconciliation with North Korea over North Korea’s denuclearization or the South Korea-U.S. alliance. He wrote that he “came to understand” this, but the subtext seemed to suggest that he regarded it as a misguided notion.

He also expressed his frustration with the Moon Jae-in administration. He criticized how left-wing groups attacked him for being of Japanese descent and led protests calling for his “decapitation,” yet the police did not take strong action. “The Blue House never mounted the bully pulpit to insist that this racist taunting of the Ambassador of South Korea’s only ally be ended,” he wrote, emphasizing “only” in italics.

Harris also pointed out the contradiction in left-wing media mocking his mustache by comparing it to that of a Japanese colonial governor. He noted, “These same people who were offended by mustache ignored the fact that many of Korea’s independence leaders in the movement against Japanese occupation sported mustaches as well.”

There is no diplomat who can win over politics

Policy changes due to a shift in government often pose a burden and a disruptive factor for foreign diplomacy, which requires consistency. This is an inevitable situation in both Korea and the U.S., where governments change periodically through elections. However, for diplomats, it can be a source of frustration.

The book introduces a scene just before the inauguration of the Kim Young-sam administration in 1993, where U.S. Ambassador Gregg meets with Kim Chong-hwi (1991-1993), President Roh’s National Security Advisor.

Kim said: “I wish we had had one more year to work together. If we could have kept the same people in Washington and Seoul working on the North Korean problem for twelve more months, I think we could have solved it.”

Kim’s view, which places a higher value on Roh Tae-woo over Kim Young-sam in terms of pragmatic diplomacy, is evident here. Gregg also praised the leadership of Roh and George H.W. Bush, which strengthened the U.S.-Korea relationship, and noted that although it was brief, inter-Korean relations had also flourished. However, as Gregg pointed out, no diplomat can win over politics.

Harry Harris, in contrast, defined the role of an ambassador as an implementer of policy, not a policymaker. In Korean, the word for “ambassador” means “great messenger,” not “big doer.”

That said, ambassadors didn’t simply follow the orders from their home country blindly. When the Carter administration’s decision to withdraw U.S. forces from Korea was announced in 1977, Richard Sneider resisted by delaying the implementation of the policy rather than complying with it. Later, William Gleysteen, who served as ambassador in 1979, persuaded President Carter for 30 minutes in the president’s limousine to reconsider the troop withdrawal.

Korean ambassadors to the U.S. were also keenly aware of the differing perspectives between the two countries. Lee Hong-koo (1998-2000) pointed out that the North Korean engagement under President Kim Dae-jung and his inner circle did not follow proper procedures, leaving the ambassador to the U.S. isolated and uninformed. He recounted that when he criticized North Korea’s Kim Jong-il regime at an event in the U.S. in 2000, the South Korean government was not pleased.

Han Sung-joo (2003-2005), who served as the ambassador under President Roh Moo-hyun, faced even greater challenges. Roh Moo-hyun was busy explaining to the Bush administration that he was not anti-American.

It was even harder to convince the U.S. about Roh’s belief that North Korea would give up its nuclear program if security concerns were alleviated. From the outset, Roh was more concerned about the possibility of military conflict arising from a preemptive strike by the U.S. on North Korea, rather than focusing solely on the North Korean nuclear issue. Han, who had always been reserved, characterized Roh’s policy as “premature” and ended his remarks with the somewhat sharp qualifier: “at best.”

‘The U.S. president should have apologized for anti-American protests’

This book delves significantly into the perceptions of U.S. ambassadors regarding anti-American sentiment in South Korea. Several ambassadors experienced invasions of their residences by protesters. They had to become accustomed to slogans like “Yankee go home” and even public burning of effigies of the ambassador. They largely attributed this deep-seated animosity to the belief that the U.S. had supported Park Chung-hee’s authoritarian regime, Chun Doo-hwan’s coup, and the Gwangju massacre.

Gregg also sensed a sense of betrayal among Koreans toward the U.S., similar to the feelings of betrayal Hungarians felt when the U.S. did not intervene during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

What stands out is Thomas Hubbard’s regret about not responding more actively to anti-American sentiment. He reflected on the tragic incident in June 2002, when two South Korean schoolgirls, Shin Hyo-sun and Sim Mi-seon, were killed by a U.S. military vehicle.

“My greatest regret in handling this incident is that I did not push hard enough for a presidential apology immediately after the incident occurred,” Hubbard wrote. “I fully expected that a Korean journalist would ask a question in Washington that would provoke an apology from the White House spokesperson, if not the president himself. I am still mystified that that did not happen.”

At first, the incident did not receive much media attention due to the World Cup excitement. After the World Cup ended, the news spread, and the incident eventually escalated into large-scale protests. Hubbard believes that public sentiment against the U.S. played a role in the election of Roh Moo-hyun later that year. While Roh’s opponent Lee Hoi-chang initially set the agenda by participating in candlelight protests, it was Roh who ultimately benefitted, reminding us of a memory that even many Koreans might have forgotten.

Diplomatic rhetoric and varied perspectives

There are some considerations to keep in mind before reading this. Since the book was written by the ambassadors of both countries, it is not free from diplomatic rhetoric. It’s up to the reader to carefully sift through the content. The authors seem overly cautious in their assessments of individuals from the other country.

U.S. ambassadors with extensive contacts in Korean politics might have provided more honest evaluations of the “three Kims” (Kim Dae-jung, Kim Young-sam, and Kim Jong-pil), but such evaluations are hard to find. For instance, Stephen Bosworth (1997–2001) described Kim Dae-jung as a “canny operator” when explaining U.S. concerns about the Sunshine Policy. Whether this is a positive or negative connotation is up to the reader’s judgment.

In contrast, Thomas Hubbard’s cynical remark that the only similarities between Roh Moo-hyun and George W. Bush were their age (both were born the same year) and lack of international experience stands out as bold.

With many contributors, there are noticeable differences in the length and style of writing. Some writings dramatically portray the dynamics of the diplomatic scene, while others read like dull administrative documents. Some authors rehash widely known facts vaguely, while others provide detailed accounts of previously unpublished information. While all the writings can be praised for their adherence to facts, the resolution with which these facts are presented varies across the works.

The foreword was written by former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. She evaluated the book by stating that it “explores the history of the relationship between our two countries through the eyes of the people who nurtured it.”

The publisher, KEI, introduced the book on their website as “a unique case study of one of the world’s most important bilateral relationships.” It further stated, “Their [ambassadors] candid stories provide insight into how diplomacy really works against the background of often dramatic events spanning 75 years.”

Meanwhile, KEI will host a discussion on the prospects of the U.S.-South Korea relationship and the experiences of former U.S. ambassadors in Seoul, including Thomas Hubbard, Christopher Hill, Kathleen Stephens and Harry Harris. The event will take place at 6 a.m. (9 a.m. Eastern Time) on December 6 and will be broadcast live on KEI’s YouTube channel from their office in Washington, D.C.

BY YOUNGNAM KIM [kim.youngnam@koreadaily.com]