Movies directed and produced by Korean-American filmmaker Seayoon Jeong are garnering attention in the U.S. With a bachelor’s degree in political science from University of Pennsylvania, a master’s in film from Columbia University, and another in government from Harvard University, Jeong has contributed to over 30 films as a producer and director.

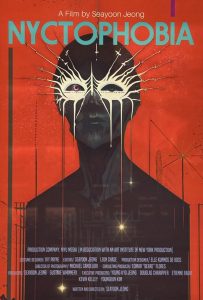

In 2020, her film “Breaking the Silence,” which addresses the issue of comfort women, was an Oscar contender for Best Live Action Short Film category. Earlier this year, Jeong released “Nyctophobia,” a movie based on her personal experiences. The film delves into the emotional journey of a protagonist who fears falling asleep due to recurring nightmares.

According to IMDb, Jeong has won 68 awards and received 26 nominations at film festivals worldwide.

In an interview with the Korea Daily, Jeong highlighted the challenges faced by minorities in the predominantly white American film industry. She explained that Asian Americans and other minority groups struggle to break into the mainstream. Experimental films, which often defy traditional storytelling norms and are her current primary focus, receive less attention than mainstream, audience-pleasing projects.

While she aspires to win more prestigious awards as a director, Jeong emphasized her commitment to creating films that align with her values. She stated that she has no intention of selling her soul or compromising her beliefs, emphasizing her dedication to pursuing a unique vision in filmmaking.

The following is an edited excerpt from the interview:

– You changed your major from political science to film. What made you decide to switch?

“I loved political science when I was in high school, so I really wanted to pursue politics as my career. But I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a politician or work behind the scenes. I majored in political science in college, but I couldn’t see myself working for politicians, especially after seeing corruption. I also interned at a law firm, but the work itself was really mundane and boring. Highlighting phone records and reviewing papers wasn’t for me, so I decided not to pursue that path.”

– Did studying political science help with your film projects?

“I still believe there’s a strong connection between politics, social change, and the arts, including film. Some people don’t see that connection, but I think movies—or even music—can be tools to make a difference. A lot of people don’t know much about the Asian, African American, or Latino communities, even though the U.S. is supposed to be a melting pot.”

– Is this why you’ve mentioned wanting to focus on giving “underrepresented people” a voice?

“I wanted to create content for these people to raise awareness about different issues—not just Asian American issues but broader ones too. I feel like many Asian people from Asia don’t really understand this. For example, I’ve met people from Taiwan or Japan who didn’t realize they were considered minorities here.

Globally, Asia is the largest continent, and populations like Chinese, Koreans, and Indians are among the largest in the world. So, we’re not minorities globally, but in America, society makes you feel like one. If you look at the media landscape, especially movies and music, even though there’s K-pop now, it’s still just one genre. It doesn’t represent the whole country.”

Challenges of representation in Hollywood for minorities

– Is it the same situation in the film industry?

“Asian Americans are often portrayed in a specific way, and you have to follow a certain narrative to be noticed. If you’re not that person, people question what you’re doing. I want to break that mold for Asian Americans and other underrepresented groups—not just in movies, but also in TV shows and everything else. On platforms like Netflix and Hulu, there are more shows and movies coming from Korea and Japan now, and I know Korean content is very popular. But it’s still about Korea, not about Korean Americans.”

– What kind of hardships do Asian Americans face in the film industry?

“It’s not just about actors, actresses, or extras; behind the scenes, it’s still very much dominated by White Americans. Even finding makeup artists can be a challenge. I had a really hard time while making “Breaking the Silence” because I wanted a makeup artist who knew how to work with Asian features.

Many makeup artists know how to work with Black or White people, but not Asians. Our eye shapes are different, and they don’t know how to apply makeup properly for us. As a result, Asian people can look weird or less attractive compared to their counterparts in the media. For “Breaking the Silence,” I had to find someone from Italy, and she was much better than anyone else I had met.”

– Do you think Asian people in your industry are underrepresented?

“Yes. When it comes to Asian American actors, many non-Asian filmmakers—especially White American filmmakers—want them to put on Asian accents to represent Asian Americans. But there are so many different types of people. Not every Asian American has an accent. There are second- and third-generation Asian Americans who are born and raised in the U.S. Yet we’re often labeled as one group, portrayed in a one-dimensional way. And it’s not just us—Latinos and even Jewish people face similar stereotypes. It’s something people have to fight against in the movie industry, and even in the music industry.”

– At the same time, it seems like there is more exposure to diverse Asian cultures in the United States.

“I think that’s mostly because of K-pop. K-pop’s presence has helped shape people’s perceptions of Asian people, to some extent. But it’s still just K-pop. If you go to places like Utah, they don’t know much about it. It’s mostly California and New York where K-pop has made an impact. Still, it has created a certain narrative for Asian people, especially Korean Americans.”

Breaking the Silence: Addressing comfort women through a broader lens

– If you were to choose the film that means the most to you, what would it be? And what was it like working on the project?

“Breaking the Silence. Writing it took a long time—about three years to get the story right. I knew the story, but many depictions of comfort women are one-dimensional. They’re shown on the front lines of war zones, attacked by Japanese soldiers, crying—and that’s it. I wanted to delve deeper into their lives, especially what it was like for them in those camps. I initially wrote a full feature script, but I wasn’t sure how the public would receive the story. So, I condensed it into a short film.”

– You seem to approach the issue more broadly than other comfort women stories.

“Yes. Many people don’t realize that women from Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, and even Australia were also captured by the Japanese. In South Korea, the focus seems to be only on Korean women. While it’s true that most of the victims were Korean, there were women from other countries as well, including white women from Australia.

I wanted to highlight this as a global issue. Making it more global could help gain broader support from organizations like the UN or countries like the U.S. Right now, the focus is too narrow, and the numbers are too small to gain support from countries like the U.S.”

Nyctophobia: Turning personal fear into experimental art

– What is your latest project, and can you briefly explain what it’s about?

“It’s Nyctophobia. That’s the fear of the dark—an anxiety disorder where people feel terrified in darkness. People with this condition can’t sleep with the lights off. The severity varies; some can sleep after a few days, while others can’t at all. Children often have nyctophobia to some degree. I actually had it when I was younger, but it went away. Then, during the pandemic, for some reason, it came back.”

– Is that why you decided to make this film?

“[At the time] I didn’t even think I could keep working on movies. Everything was shutting down, and people were leaving the industry. I wanted to make a movie, and if I had to leave the industry, I thought, ‘this would be it.’ I wanted to create something based on my own experience during the pandemic, which was very emotionally and psychologically intense.”

– I watched the trailer, and it seemed pretty scary. Is the whole film a horror story?

“I wanted to explore what happens to people suffering from nyctophobia. It’s an experimental movie, so there’s no dialogue—nothing. It’s just one character going through the motions, having nightmares, or entering a dreamscape where she encounters her enemy—or her nightmares, for that matter. The whole saga is about her trying to fall asleep. It’s not for everyone, because, as I mentioned, there’s no dialogue.”

– One columnist described you as an experimental filmmaker. Do you agree with that?

“I like the format. In the U.S., if you want to write a screenplay, for example, you have to follow a three-act structure—the first act, the second act, and the third act—for whatever reason. I don’t like limitations in general. During the pandemic, I was able to create content using stock footage or whatever I could get since I couldn’t go out and shoot. But I still wanted to create something, and along the way, I found my voice and discovered something I liked.”

Staying true to integrity in filmmaking

– Is it still the same situation now?

“Before, or even now, as a filmmaker, you have to create something the industry wants. You can’t always make what you want because if your story doesn’t sell, it won’t make it to theaters. You have to find something that’s more likely to be received well by the public—or at least by the industry. And that’s okay, because as a filmmaker, you have to survive and make money. But along the way, I discovered that experimental formats and even poetic movies are amazing. The idea of having no strict format—being able to do whatever you want and create your own space and content—is very appealing to me.”

“That’s challenging. Right now I’m independent. You have to, you know, write a story for them [big companies] and they have to give you maybe approval. And you cannot just write a story based on your understanding of like the world. You have to follow their rules or their demands actually so because of that I know people who don’t want to work with the studio system.

I mean they make a lot of money but the same time but for some people that’s why they want to be independent. Ultimately, it all comes down to money and funding. If you want to be an independent filmmaker, you can do fine—I think I’m doing fine. But if you want to make a profit or aim for something like the Oscars, you have to compromise and do things the way they want. That’s the trade-off.”

– What is your goal in the near future? Are you going to continue making the films you like, or will you change your style?

“Like any other filmmaker, I want to win something significant, but at the same time, I want to raise people’s awareness. I don’t want to make a movie that lacks meaning or a message. I want to keep making films like that. I really want to represent Asian Americans and other minority communities in a better way.

I also want to achieve something more significant, but I don’t want to compromise myself. Among my colleagues here in the U.S., there’s this saying: ‘Don’t sell your soul.’ I don’t want to sell my soul. I want to maintain my integrity while striving to achieve something meaningful.”

BY YOUNGNAM KIM [kim.youngnam@koreadaily.com]