Exploring the North-South ‘Spy War’

Part 1: The life and times of North Korean spy Kim Dong-sik

[Second in a series]

March 18, 1981, Pyongyang’s Daedong River Station at dusk.

Kim Dong-sik had been summoned by the Workers’ Party. After a seven-hour train journey from Haeju, he arrived in Pyongyang. He was an 18-year-old fresh graduate of Namchang High School from Yongyeon, South Hwanghae Province. A Central Party official met him at the station and took him to a 10-story guesthouse opposite the People’s Cultural Palace in downtown Pyongyang.

A senior official from the Party’s External Liaison Department (now the Bureau of Cultural Exchange) greeted him and shared dinner. After the meal, Kim was called into the drawing room.

“From now on, comrade, you will join the ranks of South Korean revolutionaries, thanks to the high trust and consideration of our beloved leader, Comrade Kim Jong-il. You will study at the Keumsung Political Military Academy for the next four years,” the official informed him.

The news hit Kim like a thunderbolt. An institution designed for training spies? The past year, spent competing with thousands of other students while traveling between Yongyeon-gun, Haeju, Hwanghae Province, and Pyongyang, flashed before his eyes. After numerous interviews and physical examinations, he had been selected as one of six students nationwide. He had secretly hoped to be chosen as a personal bodyguard for Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. His youthful dreams were shattered.

Training as a South Korean Spy at Keumsung Political Military Academy

Episode 2: Living to Die

Keumsung Political Military Academy (renamed Kim Jong-il Military and Political Academy in 1992) was a university he had never heard of. The fact that he was admitted without exams left him bewildered. Refusal was not an option, given his earlier pledges of loyalty to the Party during multiple interviews.

[18-year-old Kim Dong-sik: From trainee to human weapon in North-South spy war]

“What do you want to do in the future?” a Party official asked during an interview.

“I want to become an Air Force pilot or study at a university,” Kim replied.

“The Party is interviewing you for its purposes. Your answer should align with that,” the official countered.

“Then, I will do as the Party directs,” Kim conceded.

“That’s the correct answer!” the official affirmed.

Thus, he could not oppose the Party’s decision to make him a South Korean revolutionary. Without giving him a chance to respond, the External Liaison Department official issued further instructions: “During your studies, use the alias ‘Park Seung-guk.’”

This directive was meant to have Kim erase his personal identity. The existence he had known for 18 years vanished. That night, Kim was transferred to Keumsung Political Military Academy. His fate as a South Korean revolutionary, or spy in South Korean terms, was sealed.

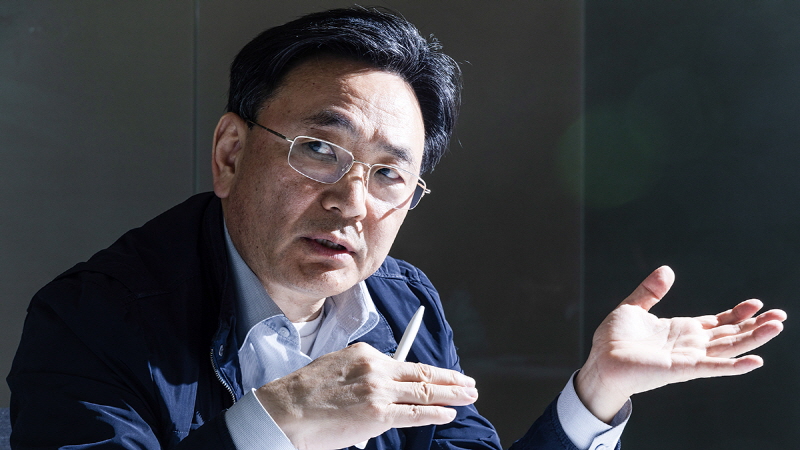

Kim recounted his bewilderment during an interview at the JoongAng Ilbo office in Seoul last April. Since late February, the JoongAng Ilbo team has been tracing Kim’s life through face-to-face and social media interactions.

“I had never heard of Keumsung Political Military Academy. I never imagined I would become a spy. At that time, the existence of the university, which trained operatives for missions involving South Korea, was a closely guarded secret,” Kim explained.

A destiny of living to die

On his first night assigned to a dormitory at the university, Kim experienced mixed emotions. First, he felt a sense of honor. Keumsung Political Military Academy was North Korea’s top university, unique in its direct selection of students by the Workers’ Party, unlike Kim Il-sung University which required exams.

The selection process was stringent, vetting students’ backgrounds, physical and intellectual capabilities for over a year. Out of the entire Hwanghae Province, only one student was selected, and that was Kim.

While Kim Il-sung University is often regarded as the top prestigious institution, this perception is flawed. The Workers’ Party first selects the nation’s top students, and then, six months later, Kim Il-sung University and other universities choose their students through exams and interviews. Kim took pride in having passed through such a narrow gate.

Secondly, he felt fear. The phrase “South Korean operative” was a euphemism for North Korean spies involved in South Korean affairs. Among North Korean residents, it equated to death. Tales of operatives going to South Korea and never returning were common. Accepting his fate of eventual death was overwhelming for a teenager.

Death, being an inexperienced event, instilled greater fear. But Kim, being too youthful to give in to despair, decided to live within the absurd reality of living to die.

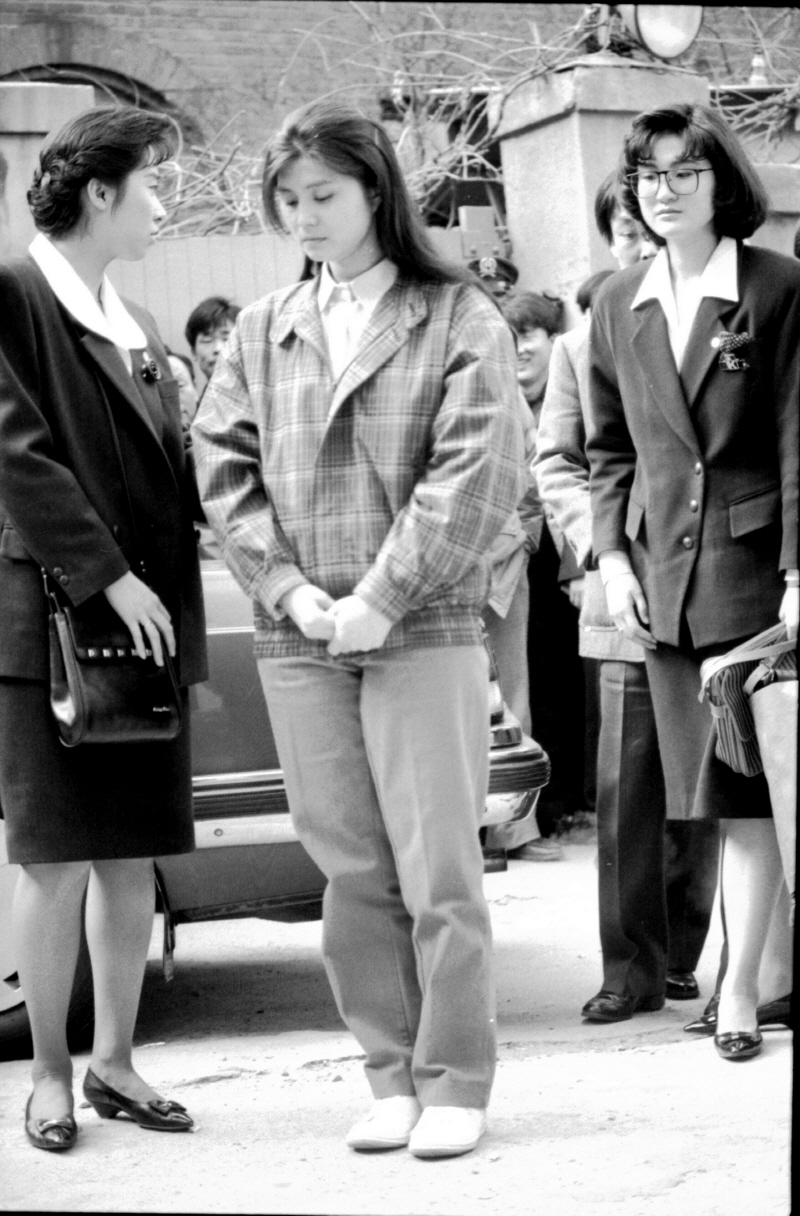

KAL 858 bomber Kim Hyon-hui: A fellow alumni

Kim was placed in the Special Forces Department, one of four departments under the Combatant Department, which had about 700 students, with 90 in his class. Daily, from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m, they engaged in classes, martial arts, jogging, and military training.

The curriculum was optimized for South Korean operations, consisting of two faculties: the Combatant Faculty, which trained students annually for four years, and the Agent Faculty, which conducted intensive training for social professionals for 6 months to 1 to 3 years. Kim Hyun-hui, the bomber of Korean Air Flight 858 in 1987, was recruited from Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies and trained at Keumsung Political Military Academy.

Kim’s training as a combatant under the External Liaison Department and later as an operative made him a unique case. His class consisted of 200 students, but only 6 were operatives.

The covert training of the Agent Faculty remained a classified matter. The following accounts are based on Kim’s experiences in the Combatant Faculty.

Education goals and ideology

The education goals were clear: to produce “revolutionary warriors” equipped with both intellect and physical prowess in the style of North Korea. The aim was to instill a strong resolve in students to carry out the South Korean revolution through agents and combatants equipped with Juche ideology and steel-like physical strength.

“Even today, most North Korean residents are aware of the existence of agents sent to South Korea but are unaware of how they are selected, educated, and trained,” Kim explained

The veil of secrecy is now lifted. The curriculum, comprised of theoretical education and practical training, focused on nurturing elite spies. The training followed four principles for creating “South Korean revolutionaries.”

The first principle is to understand the enemy to achieve victory. The curriculum included theoretical subjects such as history, geography, Chinese characters, English, humanities, economics, military science, mathematics, physics, and chemistry. While it appeared to foster cultural knowledge, the primary focus was on South Korean operations. Key subjects included Chinese characters, South Korean newspapers, and the political landscape in South Korea. Kim Dong-sik testifies:

“There was a ‘South Korean Newspaper’ distributed weekly or monthly. It was a 4 to 8 page compilation of important articles from South Korean daily newspapers, detailing social and political news. It included sources like JoongAng Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo. Before deployment, it served as a practice to understand ‘the reality of South Korea.’ At that time, newspapers had many Chinese characters, which is why they taught Chinese characters. We studied using dictionaries.”

The ‘South Korean political situation’ course explained the organization and operation of South Korea’s political and social systems. ‘Geography’ involved drawing South Korea’s map and marking highways, railways, mines, and power plants as test questions.

Military training

In his fourth year, Kim Dong-sik participated in a one-month “South Korean National Army Training,” wearing South Korean military uniforms and adhering to the daily schedule of the its army, including roll calls, drills, rifle training, and bayonet exercises.

They even experienced South Korean military punishments like “Wonsan bombing” and learned military songs like “Real Men” and “Private Kim of the Army.” The training simulated scenarios where operatives disguised as South Korean soldiers would infiltrate South Korea.

Courses in mathematics, physics, electrical engineering, chemistry, and nuclear engineering were not purely academic. They provided strategic knowledge for sabotaging key South Korean infrastructure like nuclear and other power plants. Questions like “Where to strike to completely stop a power plant?” were part of the lessons.

Ideological indoctrination

Second principle is to achieve ideological reinforcement. Throughout the four years, students learned the revolutionary history of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, Juche philosophy, and Kim Il-sung’s military theories. They were indoctrinated to sacrifice their lives for the Kim family. Kim Dong-sik recounts a shocking aspect of the curriculum reminiscent of a suicide squad:

“There was a term ‘revolutionary self-destruction spirit.’ Lectures on Juche philosophy and Kim Il-sung’s ideology emphasized that in the worst-case scenario of being captured by the enemy while performing a sacred mission for the South Korean revolution, one must end their life through revolutionary self-destruction as an act of loyalty. This was presented as the essence of revolutionary leadership and revolutionary self-destruction spirit.”

Third principle was to train like Spartans. Marching was not just walking with equipment; at Keumsong Political Military Academy, it was running with a 20 kg sandbag every evening for 10 km. Every Saturday, they ran 20 km, and on the last Saturday of each month, they covered a marathon distance (40 km) with a 20 kg sandbag within four hours.

Martial arts training, mixing Taekwondo, Judo, Hapkido, and self-defense, was intense. They trained four to five hours daily for four years, progressing from basic kicks in the first year to random full-contact sparring in the fourth year.

They also endured extreme physical challenges, like crossing the Daedong River in mid-winter with 30 kg equipment and a 150-ri (60 km) forced march through mountains.

Fourth principle was to train to become human weapons. Students trained in thrilling scenes reminiscent of spy movies: riding Honda motorcycles and Nissan jeeps with 750cc four-cylinder engines, steering ships, climbing tall buildings, and jumping onto moving truck beds.

Knife throwing involved hitting a 40 diameter target from 10 meters. They used chopsticks, kitchen knives, and axes as throwing tools, practicing escaping danger in places like restaurants by throwing whatever was at hand.

Most students were trained as sharpshooters, using Soviet TT pistols, AK rifles, RPG-7 anti-tank rockets, and Czech submachine guns in various shooting positions. Sniper training involved hitting moving targets from atop a steel tower. Kim Dong-sik shares his experience:

“In my senior year, I shot about 200 rounds daily, shooting 50 rounds each from a rifle and a pistol over a 2 km course while running and taking different shooting positions. I scored 95 out of 100 with the AK rifle and 97 out of 100 with the pistol, achieving top scores.”

The reality vs. the fantasy

The Keumsong Political Military Academy did not seek to mold muscular figures hardened by extreme military training. The goal was to create human weapons with the physical endurance to withstand extreme training, combined with ideological commitment and strategic knowledge, capable of performing terrorist acts and special operations with precision. They aimed to produce human weapons ready to sacrifice their lives, more akin to Jason Bourne than James Bond.

However, the reality was harsh. For four years, there were no vacations, visits, outings, or leaves, completely isolated from the outside world. It was a prison-like environment dominated by the dictatorship’s will to create human machines for South Korean operations.

“In South Korea, there’s a tendency to downplay North Korea’s hacking or nuclear development capabilities, viewing it as a poor country,” Kim said. “However, the Kim Jong-il Political Military Academy is a vivid example showing that in North Korea’s dictatorship, if the leader desires, they can mobilize all the needed geniuses and intensively invest them in desired projects with frightening focus.”

Adapting to South Korean society

Kim Dong-sik gradually overcame the fear of death, drawing strength from the experiences of professors and instructors who had infiltrated and safely returned from South Korea. He gained confidence from the fact that “not all operatives die.” His primal survival instincts helped him endure the four years.

In early 1985, he passed the national graduation exams in five subjects: Kim Il-sung revolutionary history, Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il’s writings, information science, illegal tactics, and special tactics. By May, he returned to the External Liaison Department and was formally appointed as an operative to be sent to South Korea.

But it was not over. Kim Dong-sik faced another hurdle: sealed education and training to adapt to South Korean society awaited him. He was given a special mission:

“Become a South Korean.”

(To be continued)

BY DAEHOON KO, MINSANG KIM, YOUNGNAM KIM [ko.daehoon@joongang.co.kr]