By Samuel K. Son

The author is Project Manager at the Boeing Company and Senior Adjunct Professor at the University of La Verne.

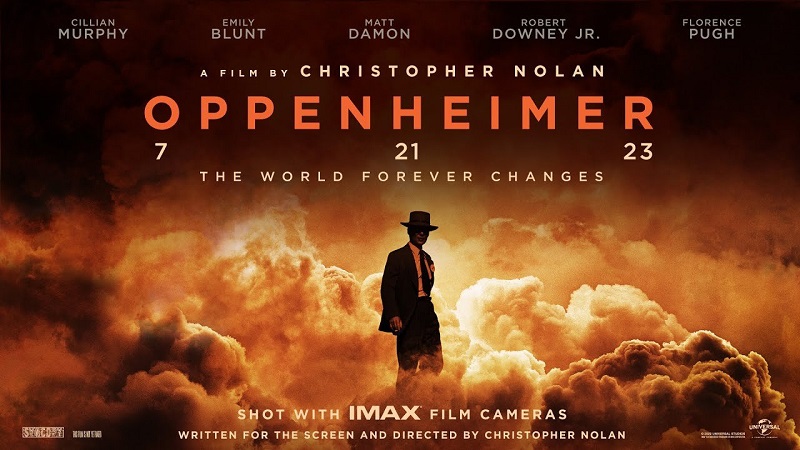

Recently, I watched the film “Oppenheimer.” Spanning three hours, it provides an intimate portrayal of the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who spearheaded the development of the world’s first nuclear weapon. The movie highlights his psychological battles following the deployment of these weapons and his tussles with being branded a communist during the height of McCarthyism.

Hailing from a privileged German-Jewish lineage, Oppenheimer completed his undergraduate studies with summa cum laude from Harvard in just three years, and later pursued graduate studies in Cambridge, U.K. However, his academic journey in Cambridge was halted due to a severe nervous breakdown and subsequent bouts of depression. In 1926, he transitioned to the University of Göttingen in Germany, delving deep into theoretical quantum mechanics under Max Born and earned his Ph.D. in a mere nine months.

As World War II commenced, anxieties over Germany’s potential atomic capabilities led the U.S. government to initiate the Manhattan Project in 1942. Oppenheimer, playing a pivotal role, ardently led this effort. Yet, the devastation wrought by the atomic bomb haunted him. Consistent with his pacifist leanings, he later staunchly contested the creation of the even more potent hydrogen bomb. His stance led to his increasing ostracization by the U.S. establishment.

While Oppenheimer was never formally affiliated with the Communist Party, his close associations, (which included his best friend, a member of the Communist Party USA), and his initial romantic interest, (Jean Frances Tatlock, a communist sympathizer) found him mingling in communist circles and donating to related organizations. The Soviets’ subsequent development of atomic and hydrogen bombs led to Oppenheimer’s vilification as a communist and a purported Soviet spy, culminating in his public office ouster. Reflecting on his role in nuclear armament, he somberly quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

During these tumultuous times, Dr. Albert Einstein penned a poignant letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He wrote, “The idea of achieving security through national armament is, at the present state of military technique, a disastrous illusion.” Einstein further advocated, “On the part of the United States this illusion has been particularly fostered by the fact that this country succeeded first in producing an atomic bomb. The ghostlike character of this development lies in its apparently compulsory trend.” For a peaceful coexistence and even loyal cooperation of the nations, Einstein proposed a three-fold approach: 1) solemn renunciation of violence (not only with respect to means of mass destruction), 2) a supra-national judicial and executive body empowered to decide questions of immediate concern to the security of the nations, and 3) peaceful cooperation based on mutual trust.

Today, the specter of nuclear weapons looms ominously over the Korean Peninsula, exacerbated by North Korea’s unrelenting provocations. Some political factions even endorse the idea of independent nuclear armament, aiming to galvanize conservative sentiment. However, this path is fraught with complexities. Embracing nuclear technology would necessitate South Korea’s exit from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), mirroring North Korea’s move. This decision would inevitably lead to confrontation with both the U.S. and China, the latter potentially retaliating through trade measures.

Indeed, the issue of nuclear armament transcends regional concerns, having profound global implications. It’s imperative for South Korea to introspect on the profound emotional agony that Dr. Oppenheimer endured and to heed Dr. Einstein’s pacifistic counsel to President Roosevelt.

![Deeper-I, Efinix sign deal to develop world’s first AI-FPGA single-chip solution Ikuo Nakanishi, left, vice president of sales at Efinix and Lee Sanghun, right, CEO of Deep-I pose for a photo after signing MOU on March 26. [Provided by Deeper-I]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/0401-DeeperI-100x70.png)