Mr. Lee, a manager at a major construction company in Seoul, works seven days a week. His company job keeps him busy on weekdays. On weekends, the father of two college students runs a samgyetang (chicken soup) restaurant in Gwanghwamun, the central part of the capital.

“You never know when you will be kicked out,” Lee says of his salaried job. “Even though it’s physically demanding, I feel better and reassured about post-retirement life.”

Lee hired a cook and two servers. His wife and older sister run the restaurant during the week.

He keeps his side job a secret from his fellow workers at the construction company.

“No one officially admits that he or she is engaged in a side job,” Lee says, “but I’m sure many of my colleagues are doing the same thing.”

According to Lee, many of the staffers at construction companies, who have built up expertise about commercial buildings and property prices, are preparing for their retirements by investing and starting their own businesses.

“It is easier to get loans when you have a salary coming in, you know,” he adds.

Mr. Kim, another manager at a subsidiary of a leading Korean conglomerate, runs a pub in the Gangnam Station area.

He started the business as a hobby. But now he is dedicating more time on to the pub on weekends to build the business — and make it lucrative enough to support him in case he loses his real job.

One of his colleagues was found doing a similar side job and was immediately told to quit by the company’s human resource team. Kim hopes that doesn’t happen to him.

With Korea’s economy facing an uncertain future, more Koreans in their 40s with relatively stable jobs are taking side jobs or part-time jobs as insurance against being laid off or retired early.

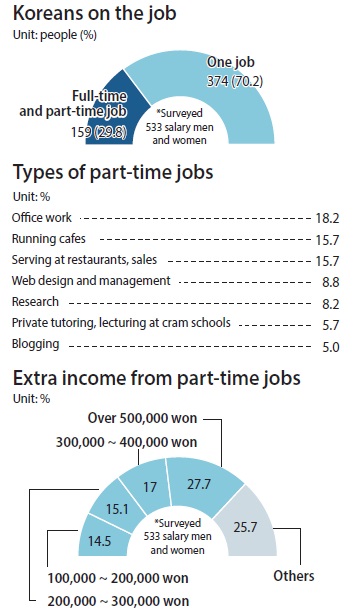

According to a recent survey by Job Korea in December, about 30 percent of 533 employed men and women said they were holding part-time jobs. About 34 percent of them were married. By age, people in their 40s showed the highest ratio of nearly 36 percent.

The highest proportion, about 18 percent, said they had side jobs doing office work. About 16 percent said they were managing cafes or Internet cafes. Another 16 percent said they were serving at restaurants or doing sales. Other jobs included designing web sites, researching, private tutoring and blogging.

Around 29 percent of the double job holders said they make more than 500,000 won in extra revenue every month from the side jobs. And 17 percent of them said they earn 300,000 won to 400,000 won. More than 50 percent of the respondents said they do the part-time jobs in order to make more money.

“As you know, people quit companies at much earlier than before,” Lee said. “Especially if it’s a large conglomerate, you never know when you will be recommended to tender your resignation. I am 50 next year, so I should prepare for the second phase of life.

“I have two kids in college and there are several years to look after them until they get married,” he said. “There is no choice but to keep working.”

According to Statistics Korea, which surveyed Koreans aged between 19 and 64 in 2014, the average retirement age for salaried people is 49.

With the baby-boom generation, born between 1955 and 1963, already starting to retire, a wave of retirements is expected to hit Korean society. And as the average retirement age gets younger, the age Koreans die continues to rise, hitting 81.9 in 2014.

There are 7.1 million baby-boomers, born in the wake of the Korean War, who are starting to retire. A second baby boom came between 1968 and 1974 after Korea’s economy started to take off. There are comprised of about 6 million people.

It has been just one and half year since Lee opened his samgyetang restaurant. Thanks to the location in Gwanghwamun, surrounded by large office buildings, the restaurant is jammed with company workers. But Lee says it is too early to reap profits because of his initial investment.

“I do have debt to repay for my apartment as well as the rent for the shop,” he says. “Rather than expecting to make money, I think this is a good chance to learn to run my own business before leaving the company.”

Lee has seen the flip side. He headlines are full of stories of people who get laid off or retired early and start their own businesses ? only to fail because they have no clue how to do it.

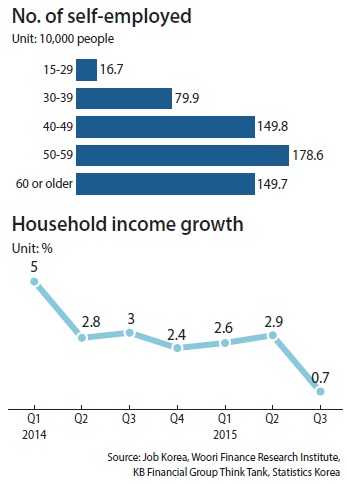

Although the total number of self-employed people in Korea is on the decrease, the number of people starting their own businesses in their 50s is rising.

As of late 2014, there were about 5.65 million self-employed people, accounting for 22 percent of the total workforce, according to the government statistics agency.

According to a report by Woori Finance Research Institute, the number of self-employed people in their 50s rose from 2.88 million to 3.28 million in 2014 compared to a year earlier, accounting for more than half the total of self-employed.

“The growth in self-employed people who are 50 or older is because of the retirements of the first baby-boom generation,” says Huh Moon-jong, a researcher at the institute. “They know they are going to live decades longer, so the retirees reluctantly choose to set up their own businesses to survive.”

But more people are failing too. As many as 49,000 self-employed men and women closed businesses in the first three months of last year, government data showed.

From 2003 through 2013, about 800,000 self-employed people closed their shops or businesses every year, according to a report by the National Tax Service.

Due to competition, the average survival rate of such businesses for three years is 53.9 percent, which means about half of Korea’s mom-and-pop businesses fail within three years.

“As the retirement wave of the first baby-boom generation is expected to continue until 2020, the number of self-employed is likely to remain at the current level, Huh says.

Another reason for having a side job is simply to earn more. Lots of families are earning almost nothing on their savings because of low interest rates. Wage earners aren’t getting big raises due to the weak economy.

Ko Young-ok, a 33-year-old assistant manager at another family-owned company, recently opened an izakaya, a Japanese-style bar, nearby his house. He is relatively young but feels the pinch due to a slow-growing salary.

“I joined some friends to open a bar,” Ko says. “I found my salary rising too slowly. I thought there should be some other way to earn more to prepare for my marriage and buying an apartment and so on.”

“Low interest rates for normal savings were another reason,” he adds. “I get little more than 200,000 won a year on the 10 million won deposited in my bank, which is very discouraging.”

Ko has kept the bar as a secret at his workplace.

“The employer might think my mind is somewhere else,” he says, “and I just don’t want to give that kind of impression at work.”

A few companies have caught up on the latest trend and actually started to help their employees branch out.

Hyundai Card is giving advice and training employees who are planning to tender resignations.

Kim Hyung-keon, 44, spent 20 years after college graduation working at Hyundai Card, where he rose to be a senior manager in sales. He quit and now runs an Italian restaurant.

It was hard for Kim to leave the company because his two children are still in high school. It was made a bit easier because Hyundai Card offered help to Kim for six months before he quit.

The company’s CEO Plan is a program started last year to help those who voluntarily retire. The program helps retirees select businesses, develop products and connects them with professional consultants to work on their management skills.

“It is natural that many companies have to lay off some employees in order to cut costs amid the protracted economic downturn,” an executive at the company said. “But it is their social responsibility to help them as much as possible even after retirement.”

BY SONG SU-HYUN [song.suhyun@joongang.co.kr]