The discovery of an 80-year-old love letter between two Koreans, who nurtured their love through the Japanese colonial rule and U.S. military regime eras to the United States, is generating interest.

When Janet Kwak, 40, of San Diego, was going through her grandmother’s possessions after her passing in 2018, she was taken aback to find 75 aged love letters in a box deep within a closet.

The majority of these were love letters sent by her grandfather, who passed away over 30 years ago, to her grandmother while they were courting in South Korea.

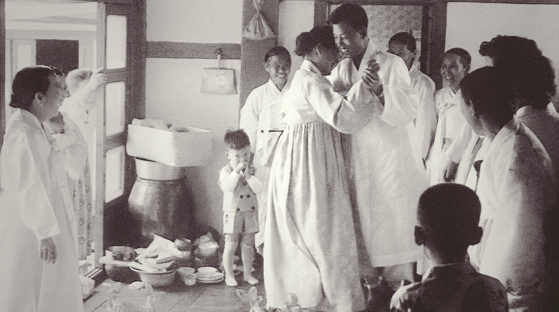

Kwak is in South Korea from October 8 to 22, retracing the romantic journey of her grandfather, Kwak Jong-ki, and her grandmother, Jung Young-sook.

“I felt the tale of my grandparents, who offered solace and hope to each other even during the oppressive Japanese colonial rule, had a profound message for all. Curiosity drove me to explore Korea alongside with my younger brother,” said Kwak.

Kwak’s grandparents, both born in 1928 and living in Daegu, met and fell in love as next-door neighbors. Their letter exchange commenced when her grandfather left for Seoul National University in 1943 and spanned the next decade.

That era saw Koreans being forcibly assimilated into Japanese culture. While attending Gyeongbuk Girls’ High School, Kwak’s grandmother was coerced into labor due to the general mobilization system.

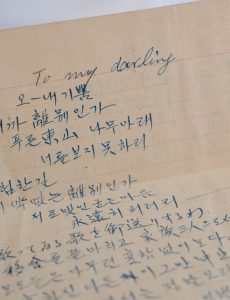

Language restrictions meant many of Kwak’s grandfather’s letters were in Japanese. Yet, the heartfelt Korean sentiments within remained untouched.

“My grandfather was a true romantic, often quoting renowned Korean poets to convey his love,” shares Kwak. “Under the American military governance, his letters consistently began with ‘To my darling’. Phrases like ‘You’re my sunshine, you’re my higher love’ were commonplace. I shared these letters on social media for translation help as they were penned in Chinese characters and Japanese. Many were captivated by his romantic flair.”

These letters, though endearing, also depicted the uncertainty of their times. “When North Korea attacked Seoul, my grandfather sent letters via friends to communicate the gravity of the situation. Yet, he’d often reference the persimmon tree at their Daegu residence to reassure my anxious grandmother and envision a brighter future for them both.”

Their love story reached its zenith when Kwak’s grandfather, after graduating, returned to Daegu to wed his beloved. The couple had two sons and later moved to the United States with their younger son, Kwak’s father, around 1989-1990. Regrettably, her grandfather soon succumbed to cancer.

“Their love story, flourishing amid adversity, instills hope for the subsequent generations,” reflects Kwak. “Second-generation Koreans might not be acquainted with such love tales. As K-pop and other Hallyu gain traction, I wish to spotlight such poignant love narratives that encapsulate an era. I’m contemplating organizing an exhibition or penning a book on their story in Korea.”

While in South Korea with her sibling, Kwak collaborates with history professor Kim Kyung-nam from Kyungpook National University. They are visiting her grandparents’ former residence and locales mentioned in the letters. As the addresses hail from the Japanese colonial period, Kwak, with Professor Kim’s assistance, liaises with the Daegu Jung District Office for the present-day locations.

“From a scholarly viewpoint, it’s crucial to examine the day-to-day lives of students during the Japanese colonial times, considering the continuity of Korean diaspora history,” said Professor Kim. “By preserving records as Kwak’s grandparents did, future generations might discover their lineage.”

BY SUAH JANG [jang.suah@koreadaily.com]

![Ex-South Korean President Accused of Trying to Trigger North Korean Attack Former President Yoon Suk Yeol leaves the Seoul Central District Court in southern Seoul after the pretrial detention hearing on July 9. [JOINT PRESS CORPS]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/0710-Yoon-100x70.jpg)