“It is I who should have visited the President… I am sorry and thankful that you came such a long way.”

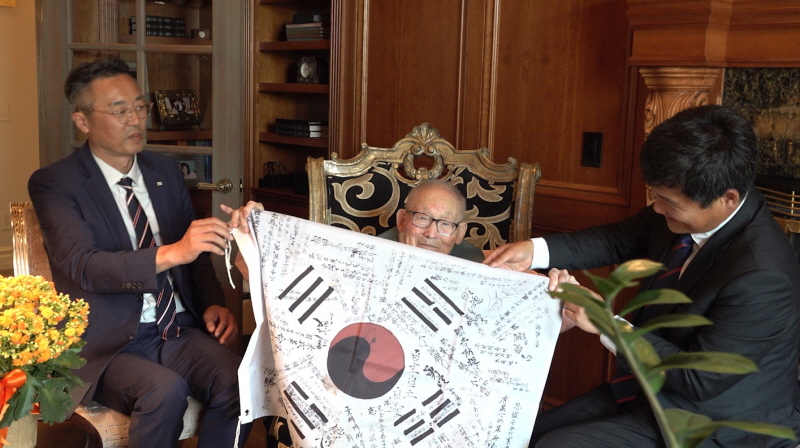

On August 9, 102-year-old independence activist Lee Ha-jeon received a plaque of appreciation, a Taegeukgi (Korean flag), and a new Hanbok, or a Korean traditional outfit, with a bowed head, repeatedly expressing his gratitude. His wrinkled hands, marked by the harshness of Japanese oppression and years spent in foreign lands, gently caressed the fine fabric of the Hanbok. Tears welled up in his deeply sunken eyes.

As the 79th anniversary of Korea’s liberation approaches, only six of the independence patriots who were decorated with honors remain alive. Three have passed away last year. The JoongAng Ilbo, a leading Korean newspaper affiliated with the Korea Daily, had the honor of interviewing Lee, the oldest among them, at his home in Sacramento, U.S.

Following the permanent return of another patriot, Oh Sung-kyu, from Japan last year, Lee is the only surviving independence activist residing abroad.

“At last, we meet our hero”

When we knocked on the door on the morning of August 9, Lee emerged, relying on a walker, accompanied by his son and daughter-in-law. As Lee Gil-hyun, an officer from the South Korean Embassy in the U.S., greeted him respectfully, saying, “At last, the Republic of Korea has come to meet our hero,” Lee grasped his hand firmly and repeatedly said, “Thank you.” After changing into a Hanbok given by a representative from Binggrae’s U.S. branch, he smiled brightly, saying, “Now, I really feel like a Korean.”

When informed that new Hanboks would be delivered to all six surviving independence activists in time for Liberation Day, Lee expressed his gratitude, saying, “It’s a truly commendable gesture.”

The Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs and Binggrae also plan to use artificial intelligence (AI) to digitally place Hanboks on photos of 87 independence patriots who died in prison in prisoner uniforms and deliver these images to their descendants.

The 17-year-old ‘crew-cut’ independence fighter

As the interview began, Lee opened an album containing photos from his teenage years, including one taken 85 years ago when he was just 17. He fell into deep thought while looking at the pictures of his young comrades.

Below are edited excerpts from the interview.

– Weren’t you afraid to join the independence movement at such a young age?

“Of course, I was scared. What power did a young student have? There was even a ‘spy’ planted by the Japanese Governor-General’s Office at the Sungsin Commercial School in Pyongyang, where I was studying. But my comrades and I formed a secret society out of pure patriotism, saying, ‘We must do something.’ We would send one or two dollars—considered a large sum back then—to the provisional government in Shanghai.”

– You were eventually captured by the Japanese and imprisoned.

“After graduating from school in Pyongyang, I continued my activities while studying in Japan. However, during an investigation into Teacher Ham Seok-heon (1901-1989) by the Governor-General’s Office, our secret society was exposed, and I was arrested in Japan and extradited to Korea. I was sentenced to two and a half years for violating the Peace Preservation Law. Including the pretrial detention period, I spent three and a half years in prison and was tortured daily for a year.”

Influences of Ham Seok-heon and Ahn Chang-ho… “To win, one must study”

Shincheon Ham Seok-heon, an independence activist from Yongcheon, North Pyongan Province, was arrested by North Korean authorities after being accused of being behind anti-communist protests after liberation. He later escaped to South Korea and became a leading figure in the democratization movement in South Korea, enduring multiple imprisonments.

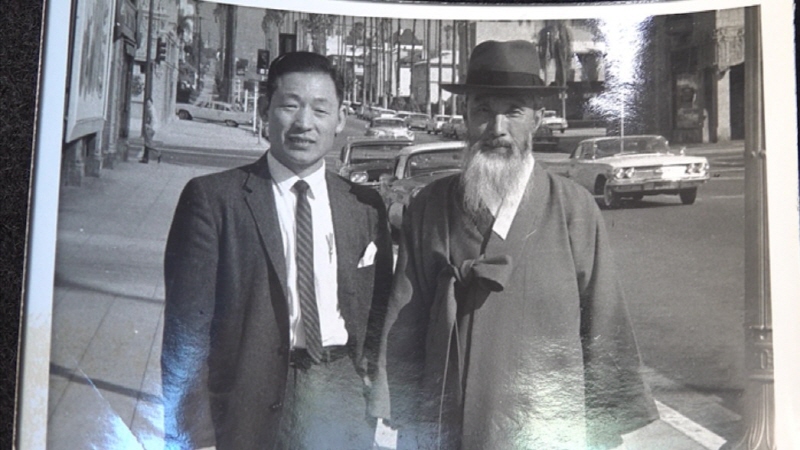

Along with Shincheon, Lee’s spiritual mentor was Dosan Ahn Chang-ho (1878–1938). As a member of the Heungsadan, Lee’s beliefs aligned with Dosan’s philosophy of “building strength through education.”

– It is said that you were greatly influenced by Ahn Chang-ho.

“It’s a long story. In his later years (around 1935), Dosan was staying at Daebosan (Songtaesan Lodge) near my home. There were police officers stationed everywhere, so we would avoid the main road and take the back road. Even after I came to the U.S., I served as the chairman of Heungsadan.”

A divided homeland… A Korean language professor for the U.S. military

After Korea was liberated and the North and South were divided, Lee fled to the South. Following Dosan’s path, he took a ship to San Francisco.

– How did you feel when you heard the news of liberation?

“I was overjoyed. But then Korea was divided into North and South. Communism from China and the Soviet Union entered the North. My father and I crossed Imjin River at night. I couldn’t agree with communism. I believed that to win, I had to study. After graduating from Yonsei University, I took a ship to San Francisco. I had only five dollars, so I washed dishes every day while studying.”

– You must have heard about the Korean War while in the U.S.

“When the war broke out, U.S. troops were sent to Korea. I became a Korean language professor at the U.S. Army Language School in Monterey and taught Korean to U.S. soldiers who participated in the Korean War. I did that job for over 30 years.”

Regarding his family in North Korea and ideological controversies, Lee waved off the questions, saying, “I know nothing about that.” When asked about his remaining family in the North, he said, “I had two younger sisters, but I don’t know if they’re alive or dead, and it doesn’t concern me. I just dislike communism.”

Lee’s family members explained, “Although he often missed his family, he never spoke of them out of concern that they might face repercussions because of him. He also refrains from discussing political issues, believing it’s better not to say anything, given his experiences.”

“Time to live as neighbors with Japan”

Despite vividly remembering Japan’s oppression, Lee now believes that it’s time for Korea and Japan to live as neighbors.

– Recently, there have been efforts to improve relations with Japan.

“Having experienced imprisonment at the hands of the Japanese, I understand their mentality well. I also got to know Americans while living in the U.S. I don’t know about the political situation, but there’s no need for us to remain enemies with Japan. We can live as neighbors now. After all, Koreans are smarter, so we can manage as neighbors.”

– What would you like to say to future generations?

“They must study. I had to work my way through school because I had no money. Although I studied, I regret that I couldn’t go beyond a master’s degree.”

A promise to be buried at the National Cemetery

In 1990, Lee received the Order of Merit for National Foundation, Patriotic Medal. Although he is eligible to be buried at the National Cemetery, he had not yet officially expressed his intention. The Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs has secured space at the National Cemetery for all six surviving independence patriots.

– Do you have any thoughts of returning to Korea after you pass away?

“I’m grateful that I’ve been recognized as a national merit recipient. I’ve heard that there’s a place in Korea for honoring such people. If I could be buried there, it would be a great honor.”

The veteran officer assured Lee that they would ensure his burial at the National Cemetery according to his wishes. Lee repeatedly asked that his gratitude be conveyed to the President. His son and daughter-in-law expressed their thanks, saying, “We’ve kept our mother’s ashes since she passed away seven years ago, hoping that she could be buried at the National Cemetery. We’re truly grateful.”

After the interview, Lee said, “I’m in such a good mood that I want to sing my favorite song.” He then quietly sang “Springtime in My Hometown,” a song that ends with the lyrics, “I long for those days playing in the fields.” Leaning on his walker, he escorted us to the door and waved goodbye until we disappeared from view, asking us to visit again anytime.

BY TAEHWA KANG, YOUNGNAM KIM [thkang@joongang.co.kr]